Wilhelminian Wiesbaden

The Wilhelmine period is considered the glorious high point of Wiesbaden's city history. Strictly speaking, this refers to the reign of King Wilhelm II of Prussia, who headed the German Empire as German Emperor from 1888 to 1918. However, the year 1866, when Nassau was annexed by Prussia and Wiesbaden lost its function as the state capital, was more decisive for the city's development. The years under Kaiser Wilhelm I should therefore be included as a historical prelude.

As in Roman times, the spa and bathing industry once again dominated the foreground. The Prussian regional council could only inadequately compensate for the loss of the government authorities of a sovereign state. On the other hand, the opening to Prussia increased the influx of foreigners to an undreamt-of extent. In 1890, more than 100,000 visitors came to the city and in the peak year of 1907, over 180,000. At the same time, the number of people settling permanently in Wiesbaden increased. The population rose from 26,000 in 1866 to 60,000 in 1888 and 100,000 in 1905, until it reached its highest level until the end of the German Empire in 1910 with 109,000 inhabitants.

In addition to the favorable state conditions, municipal policy also had a major influence on growth. With the takeover of the entire Kurhaus complex, the municipal bodies, together with the Kur- und Verkehrsverein e.V., initiated an advertising campaign that focused entirely on the natural advantages of the town. In addition to the promotion of inner-city transport services, successful efforts were made to establish favorable rail connections and a prestigious railroad station. The central water supply established in 1870, the sewerage system built in 1886, the abattoir opened in 1884 and the waste incineration plant commissioned in 1905 were all closely linked to the concept of healthy living.

The city expansion plan by city architect Alexander Fach, adopted in 1871, already laid down the basic direction: the ring road and a strictly rectangular street network with closed perimeter development and block formation opening up the depth of the site in the south and west of the historic pentagon, as well as a green, loose development of country houses in the east. Historicizing architectural styles were used throughout the 19th century. It was not until the turn of the century that a new architectural design style emerged in the form of Art Nouveau.

As industrial companies were deliberately kept away, there were basically only two groups of residents: those who lived off the income they earned elsewhere and those who served them in various ways, with the second group having to cater for spa guests as well as local residents. The upper social class clearly dominated in the villa areas. Residents of the upper classes also lived in the southern part of the city center in the areas between Bahnhofstrasse, Rheinstrasse and the Ring. In terms of comfort and social prestige, the rental apartments built there with their six, eight or ten rooms offered a real alternative to detached villas. This district was the closest to the ideal of a social mix. In the basement, the attic, the rear building and the side building, there was still room for the day laborer, the train attendant, the waiter, the coachman, the woman of the month and this or that craftsman. In contrast, the Bergkirchen quarter developed into a distinctly residential district for service personnel. The Westend assumed similar functions during the Prussian era, although as development progressed, the better-off also increasingly moved in.

A comparison of tax revenues with those of other cities also shows that Wiesbaden not only had high income and property tax revenues overall, but also the highest number of gold mark millionaires of all Prussian cities in relation to the number of inhabitants.

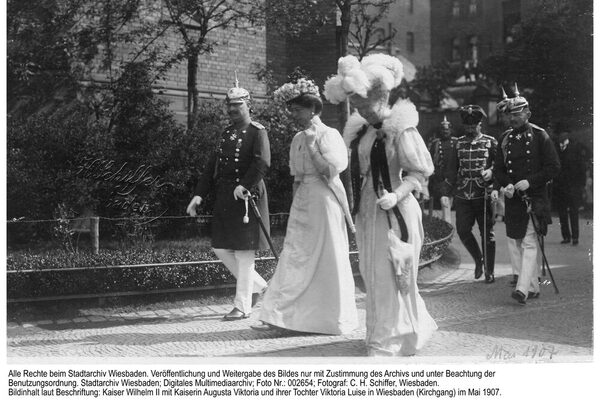

Social life was given an additional boost with the completion of the Trink- und Wandelhalle on Kochbrunnenplatz in 1890, the completion of the theater in 1894 and the opening of the Kurhaus in 1907. Sport was already a major attraction, with international tennis tournaments, horse riding, rowing, golf, field hockey and the Erbenheim racecourse, which opened in 1910, enjoying great popularity. The highlight of the annual program of events, however, was the Imperial Festival and the associated imperial visits.

Kaiser Wilhelm I had already visited Wiesbaden no less than fourteen times. Wilhelm II came to Wiesbaden officially for the first time in 1894. However, it was only with the start of the May Festival in 1896 that his stay turned into that peculiar mixture of Rhenish folk festival, social self-presentation of the aristocracy of birth and money and patriotic ruler's cult, which not only appealed to the upper classes but also to the common people. The fashionable spa and residential town increasingly became the epitome of new German imperial glory and a close alliance between the Prussian aristocracy and the newly wealthy bourgeoisie.

In the final years before the First World War, however, the town's appeal began to wane noticeably. The number of spa guests stagnated and the population declined. The war and its consequences accelerated the process, and the incorporation of the industrial suburbs of Biebrich and Schierstein in 1926 at the latest signaled that Wiesbaden had finally bid farewell to the self-imposed model of the luxury city.

Literature

Neese, Bernd-Michael: The Emperor is coming! Wilhelm I and Wilhelm II in Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2010.

Schüler, Winfried: The Wilhelmine Wiesbaden. In: Nassauische Annalen. Ed.: Verein für Nassauische Altertumskunde und Geschichtsforschung, 99/1989 [pp. 90-110].

Architectural Guide Wiesbaden. The City of Historicism, Bonn 2006.