Sewer system

In the Middle Ages and early modern times, wastewater disposal was a private task. From private properties, wastewater was discharged into streams via simple ditches, channels and pipes; faeces were collected in pits, taken away by farmers or so-called fertilizer export companies and spread on the fields as fertilizer. Around 1800, there were already around 1,500 m of brick-built sewers, but only very few of them were covered and had to be cleaned regularly. Around 1820, a twin canal with quarry stones was built under the sidewalk in the Warmer Damm area. As the population grew, so did the nuisance caused by unpleasant odors; an additional problem was the heat of the thermal water, which encouraged the development of odors. In 1863, a petition was received from English spa guests who wanted the Salzbach, the main collector of the waste water, to be arched over, as it was particularly polluted. By this time, however, great efforts had already been made to improve the sewerage system. The open streams had been arched over since 1859; master builder Alexander Fach had created 37 km of new sewers by the end of the 1860s, and the first concrete pipes were laid around 1868. However, there was a lack of uniform modern construction methods, flushing and ventilation equipment. The canals also had too little gradient. The Salzbach, which emptied its water into the Rhine below Biebrich, increasingly came into focus. Typhus outbreaks had already occurred in 1815 and 1839. In 1881-84, there were even annual typhus epidemics - with considerable negative consequences for the spa industry. The last typhoid epidemic, which claimed 59 lives, finally provided the impetus for a fundamental redesign of Wiesbaden's sewerage system.

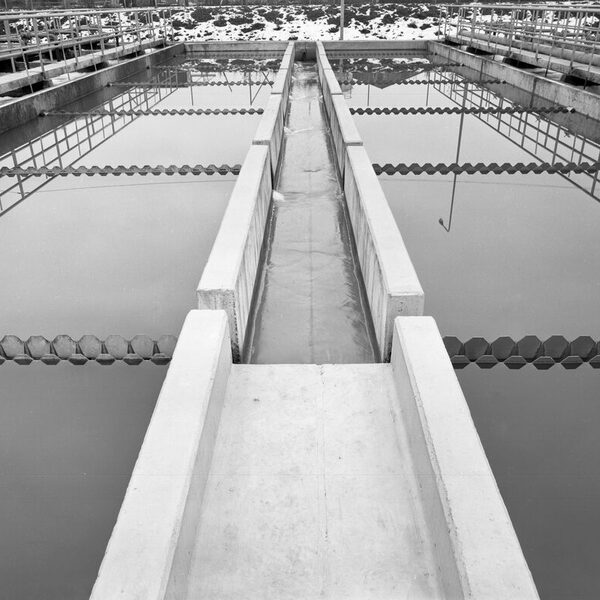

In 1885, the municipal council decided to improve these unsanitary conditions, build sewers and sewage treatment plants and introduce water closets. The engineer commissioned by the city, Joseph Brix, designed a single-pipe system, also known as a combined sewer system, which fed domestic wastewater from households and businesses and rainwater together in the same sewers to the treatment plants for purification, partly due to Wiesbaden's topographical location. The advantages over the separation systems favored today were, on the one hand, the cost savings due to the elimination of a second sewer system and, on the other hand, the inevitable cleaning of the sewers during heavy rainfall. The serious disadvantage, however, is the discharge of dirt particles from the wastewater into the nearest receiving watercourse (stream) and then to the Rhine when the sewer network is overloaded by heavy rainfall. The sewer system was one of the largest construction projects in the city; by 1908, the construction of 122 km of sewers and a sewage treatment plant at the Spelzmühle (1885) had cost around 110 million RM. 1900-03 saw the construction of the inlet sewers, mostly egg-shaped, with clinker brickwork to the Salzbach canal. The Salzbach itself was laid in an underground iron pipe channel, which led the treated wastewater into the Rhine, 100 m away from the bank in the river bed.

Wiesbaden's sewer system still functions largely as a combined sewer system today. Only in some areas of the eastern suburbs that were incorporated in 1977, such as Breckenheim, has the "Pfingstborn" development area been sewered using a separate system. Of the six eastern suburbs, Breckenheim, Nordenstadt and Delkenheim do not dispose of their wastewater to Wiesbaden, but to the sewage treatment plant in Flörsheim. Wiesbaden's sewer system has a total length of approx. 819 km, approx. 77 of which are accessible with a diameter of 120 cm. Approx. 84 km are crawlable with diameters of 80 to 120 cm. The sewer system includes approx. 22,000 manhole structures, approx. 27,000 street inlets, approx. 2,200 km of private house connection pipes, 58 rainwater overflow structures and 30 rainwater retention basins. The proportion of pure rainwater sewers in the public sewer network is 3%. In addition, there are several kilometers of so-called thermal sewers, some of which are accessible and in which the supply lines of the former and current bathing establishments are installed.

Literature

Brix, Joseph: The canalization of Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 1887.

Silberzahn, Joachim: Geschichte der Kanalisation und Klärwerk in Wiesbaden. From the 19th century to the present day, Wiesbaden 2015.