Cure in Wiesbaden

From the beginnings to the end of the 18th century

The Romans were already using Wiesbaden's saline thermal springs for therapeutic purposes. Reliable information about bathing in the Middle Ages dates back to 1232, and continuous use of the springs for therapeutic purposes has been documented since then at the latest. Up until the 18th century, the water from the thermal springs, which are among the hottest in Europe at up to 67 °C, was mainly used for bathing after cooling down.

The numerous balneological treatises published since the beginning of the 17th century attributed healing powers to a bath for a wide range of illnesses such as kidney problems, coughs, gout, musculoskeletal complaints, circulatory disorders, rashes, women's ailments, pallor and anxiety. If bathing for up to 1½ hours, bathers should only sit in the water up to their navel. To avoid catching a cold, they should wear a cap and wrap their upper body in a linen cloak. After the bath, the guest should quickly wrap themselves in warmed towels and wait in bed for the onset of perspiration.

People bathed in Wiesbaden in the bathing hostels, which can be traced back to the 15th century. The oldest include the Schützenhof (1st half of the 15th century), Bock (1486), Schwan (1471), Wilder Mann (1485), Krone (1455), Stern (1485) and Rose (1500). Only three new bathing hostels were added after 1600: Rebhuhn (1st half of the 17th century), Zwei Böcke (1618) and Sonnenberg (1735). A bathing inn consisted of a residential building and a bathhouse attached to the courtyard and had an average of five to ten rooms. More elegant houses such as the "Goldene Adler" and the "Schützenhof" had more than 20 rooms. There were at least two pools in each bathhouse, and four in larger houses. Only half of them were ever used; the hot water cooled down to the ideal bathing temperature in the remaining pools over the course of a day. The bathing pools were around 12 m² in size and approx. 60 - 80 cm deep, offering space for up to 16 people. If only one pool was available, men and women bathed together. At the end of the 17th century, under pressure from the clergy, the owners divided the pools into separate sections for men and women using wooden screens. The floors of the bathhouses were covered with sandstone slabs. Only the first house on the square, the "Golden Eagle", had marble floors. The walls were whitewashed; in the "Schützenhof", which was modernized in 1783, they were tiled with faience tiles. The roofs of the bathhouses had chimney-like openings through which the steam from the hot water could escape.

As bathing became a private, intimate activity in the 18th century, the landlords of the bathhouses converted the communal pools. Partitions divided the pools into small enclosed cells. At the end of the 18th century, these primitive bathing cells gave way to spacious individual baths in the modernized houses. After the conversion, the Schützenhof had 32 bathing cubicles with heated baskets for towels, a bench for resting and a water basin measuring approx. 2 × 1.70 m and approx. 90 cm deep.

A petty bourgeois clientele took the cure in Wiesbaden: master craftsmen, wealthy farmers, members of the municipal administration of smaller towns, journeymen and soldiers of the lower ranks. For the considerable number of poor people and war invalids who came to the spa, the costs were borne by the local community or the poor and hospital baths. The guests, who came from a radius of 50 km, stayed for a week; longer stays were rare. Nobles and wealthy citizens formed a minority.

Bathing was an important source of income for the population. While Wiesbaden maintained its unchallenged position among the south-west German thermal baths at the end of the Middle Ages, from the end of the 16th century the town faced competition from the cheaper and increasingly popular drinking spas. Especially since the rise of Langenschwalbach after 1650, the spa business suffered a dramatic slump. The town council did nothing, even though the owners of the bathing establishments had a majority on the council. The Nassau rulers, preoccupied with dynastic and foreign policy problems, also remained inactive until the end of the 17th century, unlike their peers in neighboring territories.

It was not until 1690 that Prince Georg August zu Nassau abruptly roused Wiesbaden from its slumber and ordered the expansion of the city and the renovation of the run-down spa district in the "Sauerland". As the prince had no access to the privately owned springs, he was unable to build any new bathing establishments himself and had to rely on the cooperation of the citizens. He used tax concessions to encourage them to rebuild their houses. On his initiative, the spa district was given a new center with the Kranzplatz, the Herrengarten was created outside the city fortifications, and shady avenues in the east and west of the city invited people to promenade. He commissioned balneological advertisements reflecting the latest medical knowledge and improved medical care. This package of measures soon yielded its first successes. The spa business revived slightly at the beginning of the 18th century.

The big breakthrough did not come for the time being, as Georg August died in 1721 before he could realize all the planned projects. His successors from the Nassau-Usingen line were prepared to continue promoting the spa. However, the stubbornness of the citizens made it almost impossible to push through improvements. For example, the construction of the social hall desired by the guests failed due to the fierce resistance of the spa owners. As the sovereign authorities could not count on the cooperation of the citizens, they took the initiative themselves. Just outside the town gates, they had a new English-style park built with stalls for foreign traders and a small café serving tea, coffee, chocolate and liqueurs. On summer evenings, the park was illuminated to create a festive atmosphere. Together with the adjoining avenue to the Wiesenbrunnen, which had always been a very popular walking path, the government had thus helped Wiesbaden to become an attractive recreational center.

The monotonous small-town amusements were also improved. From 1765, the authorities organized a contrasting programme with brass band concerts on the Kranzplatz and regular guest performances by travelling theatres, and in 1771 allowed gambling, which was popular in all social circles. At the same time, it embarked on a large-scale campaign to discipline the population.

Almost 300 ordinances relating to all areas of public life were aimed at educating the inhabitants to have a sense of order as understood by the authorities and to create pleasant conditions for the spa. Compliance with these regulations was monitored by an extremely efficient police force. The efforts paid off. From the 1770s onwards, the spa business picked up. In addition, numerous guests came from Mainz and Frankfurt, especially at weekends. This gave Wiesbaden an additional function as a local recreation area.

The Wiesbaden cure in the Duchy of Nassau

Soon after 1790, development stagnated. This was due to the onset of the Napoleonic Wars and the spectacular spa resorts that had been built in the neighborhood, such as Hanau-Wilhelmsbad. Spa districts of this layout corresponded to the wishes of the "good society", the leading class of nobility and parts of the upper middle classes. As the 18th century progressed, the latter paid attention to the separation of social classes and preferred the new spa districts to the baths frequented by several estates. A visit to such a spa was now less of a health cure and more of a social cure.

Immediately after the founding of the Duchy of Nassau, the state government and the ducal family agreed to establish a spa district of this new type in Wiesbaden. The new spa district was intended to provide a forum for the duchy's "good society" to present itself alongside wealthy and distinguished guests from abroad. Planning and implementation were in the hands of the government, which was thus able to realize the state's ideas uninhibited by bourgeois interests, which had blocked any initiative in the 18th century.

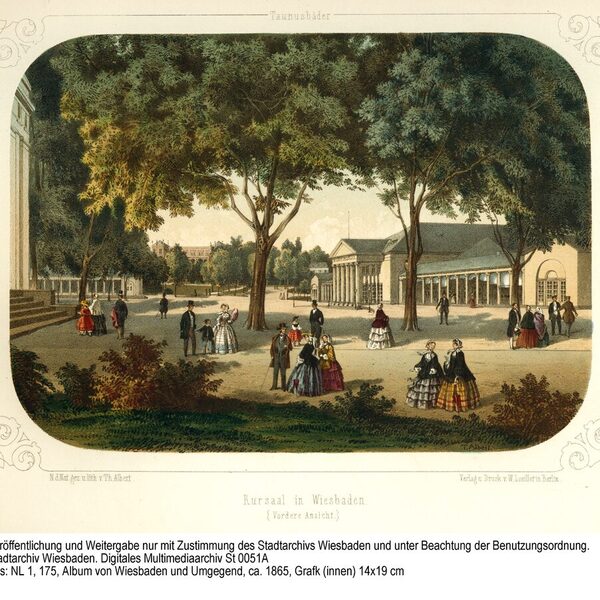

The heart of the complex, the Kursaal(old Kurhaus), which was financed by a public limited company and served exclusively as a social center, was inaugurated as early as 1810. The simplicity of the neoclassical façade appealed to the taste of the bourgeoisie, while the luxurious interior with its royal box, galleries and state rooms met the wishes of the aristocratic public for representation. The acceptance that the Kursaal found among the upper classes contributed decisively to Wiesbaden's brilliant rise. A park adjoined the Kursaal. To this end, the baroque Herrengarten, which dated back to the 18th century, was transformed into an English park according to plans by famous garden architects. In the fountain colonnade, newly built in 1810, with its exclusive stores, aristocratic society found a luxury salesroom that allowed them to demonstrate their wealth through consumerism.

In 1821, the bathhouse Zu den Vier Jahreszeiten, built by Christian Zais, opened its doors. Guests found a hotel equipped with every luxury, including bathing facilities, elegant rooms, salons and a restaurant. The hotel quickly established itself as one of the top addresses in Germany. The spa district was completed by the theater, which formed the antithesis to the Kursaal, a promenade, the later Wilhelmstraße, and a villa area, which was built adjacent to the spa area.

To ensure that guests could experience the spa as a peaceful oasis, shielded from nuisance, without disturbance or fear of crime, the authorities enacted a host of regulatory measures.

The ducal authorities were also determined to improve medical care. Scientific source analyses by well-known chemists served the highly qualified doctors appointed to Wiesbaden as a basis for drawing up detailed lists of indications. Taking into account the latest findings in balneotherapy, the range of therapies on offer was constantly expanded. The drinking cure, previously of secondary importance, was officially introduced as a spa treatment. Innovative were the various hydrotherapies, which included various forms of "Douschen", packs with the iron-containing deposits of the springs, whey cures as well as exercise and strengthening therapies.

The presence of genuinely sick people was undesirable in Wiesbaden. The sight of them should not impair the "cheerful state of mind" that doctors considered necessary for the success of the cure. Everything reminiscent of illness and death was banished from the guests' field of vision. Medical facilities were located far away from the spa district. Only special institutions that treated "clean" illnesses, such as orthopaedic conditions or eye diseases, were permitted.

Duke Friedrich August zu Nassau was quick to take away Wiesbaden's provincial reputation through targeted cultural cultivation and an appropriate entertainment program. As theatrical performances were an essential leisure activity for the "good society", he engaged his own ensemble, which moved from the provisional venue in the Schützenhof to the newly built court theater in 1827. The authorities also provided an entertainment program that was tailored to the requirements of high society. Spa music was regularly offered in the seclusion of the spa facilities from 1805. Spa taxes and additional entrance fees enabled the public to keep to themselves and listen to the military bands or foreign musicians in broad daylight at their leisure.

The dance events were a highlight of everyday life at the spa. Balls were among the major social events. Attending them was a mark of distinction. The higher classes kept to themselves at all dance events, as from 1830 strict dress codes and high entrance fees kept out the unwelcome middle classes. The exclusivity of the balls was a trademark of Wiesbaden and increased its attraction as a spa resort for the upper classes. The hazard game was also a crowd-puller. The wealthy part of the guests demonstrated their prosperity here and thus set themselves apart from other social classes. The newly established reading cabinets and lending libraries satisfied the thirst for reading and knowledge.

Road construction measures aimed to turn Wiesbaden into a new regional transportation hub. A new era began in 1839 with the opening of the Taunusbahn. As steamships had been operating regularly on the Rhine since 1827, there was a direct connection to the overseas port in Rotterdam. Thanks to these measures, Wiesbaden saw a significant increase in visitor numbers from the beginning of the 19th century. While around 10,000 guests visited the city in 1816, the number had risen to 35,000 by 1865. In terms of visitor numbers, Wiesbaden, together with Baden-Baden, was one of the leading health resorts in Europe. The proportion of foreign visitors leveled off from 10% in 1810 to around 45% in the 1850s. With around 2,000 guests (25%), the English made up the largest contingent from the 1830s to the 1860s, followed by the Dutch and Belgians. Russians and French visitors averaged 1,200 each. US-Americans only arrived in significant numbers with the establishment of a regular steamship connection overseas in 1856. The high proportion of foreign visitors and a wide variety of nationalities justifies Wiesbaden's designation as a world spa; in 1852, the city earned the nickname Weltkurstadt (world spa town).

A socio-historical analysis of Wiesbaden's visitors is not yet available. It is therefore not possible to quantify the proportion of aristocracy and middle-class visitors among the guests or their origins. It is clear, however, that since the beginning of the 19th century there has been a sharp change in the social composition of the spa public. From the petty bourgeois spa of the late 18th Weltkurstadt (world spa town).

A socio-historical analysis of Wiesbaden's visitors is not yet available. It is therefore not possible to quantify the proportion of aristocracy and middle-class visitors among the guests or their origins. It is clear, however, that since the beginning of the 19th century there has been a sharp change in the social composition of the spa public. From the petty bourgeois spa of the late 18th century, the town was transformed into a meeting place for "high society" by 1866 thanks to state subsidies.

Spa life in Prussian Wiesbaden from 1866 to 1914

The most important change for spa life after the annexation of Nassau in 1866 concerned gambling, which had been banned in Prussia for some time; the Wiesbaden concession expired in 1872. Closely linked to this was the question of transferring the spa facilities to municipal ownership. The Kurhaus, colonnades, spa facilities and the Sonnenberg ruins became the property of the city on January 1, 1873. Wiesbaden received 2.49 million marks from the spa fund and around 300,000 marks from the beautification fund to cover its new tasks. Ferdinand Hey'l was appointed Wiesbaden's first spa director. Thus, despite the end of gambling, the financial conditions were created for the targeted promotion of spa life.

The city's cultivated atmosphere not only led to a further increase in the number of spa guests, but also to the arrival of many wealthy pensioners. Wiesbaden's population passed the 100,000 mark in 1905, including 300 Goldmark millionaires. Municipal revenues increased despite the relatively low rate of taxation and formed the financial basis for the major investments of the following decades. The number of spa guests continued to rise, reaching around 80,000 in 1883, 100,000 ten years later and twice as many again by 1914. Between 1894 and 1906 in particular, further large new hotels were built.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, the improvement of the city's hygiene and infrastructure and - especially after a typhoid epidemic in the summer of 1885 claimed 59 lives - the new sewerage system in Wiesbaden were urgent issues to be resolved. The supply of clean drinking water also required considerable effort. After 1890, the number of typhoid deaths fell to a third of that of comparable large cities. The hygienic conditions in the baths were improved and aesthetically pleasing public conveniences were installed. The streets were kept clean by the nightly use of street sweepers and sweepers. The municipal abattoir, which was opened in April 1884 on what was then the outskirts of the city, also contributed to better hygienic conditions.

The gasworks on Nikolasstraße (later Bahnhofstraße), built by a private company in 1847/48, became municipal property in 1873. In the mid-1880s, it was relocated to what was then the outskirts of the city and its capacity was continually expanded. By 1913, the length of the pipe network had reached 138 km and the number of street lamps had risen to 4,258. An electricity plant was built in 1897/98 as a steam power station and supplied the electricity for the operation of the streetcars from 1900. In 1906, a waste incineration plant was put into operation with another steam turbine.

The expansion of public transportation was essential for Wiesbaden's development into a spa and major city. The three railroad stations in the lower part of Rheinstraße formed the transportation hub from which the first horse-drawn streetcar was operated in 1875 via Wilhelmstraße to Röderstraße, and later to Beau Site. In 1889, a horse-drawn streetcar ran from there via Kirchgasse to Kranzplatz and Röderstraße, and a steam train line was set up at the same time. In May 1896, the first electric streetcar line went into operation. From 1906, the streetcar connected Wiesbaden with Mainz, Dotzheim and Erbenheim; a bus service to Schlangenbad was also established. The opening of the new main railway station in 1906 "crowned the development of modern transportation" (Müller-Werth). The popular excursion destination of Neroberg had already been accessible by cable car since the fall of 1888. On December 1, 1885, the first telephone system was put into operation.

Cultural facilities were of great importance for Wiesbaden's spa life, first and foremost the royal court theater, which was inaugurated in 1894. The first Imperial Festival was held in May 1896. The largest project was the construction of the new Kurhaus, completed in 1907. Great importance was also attached to the expansion of the gardens, which were supplemented by the creation of a network of paths in the surrounding Taunus forests, both for walkers and horse riders as well as for carriages.

Large inner-city streets, such as the Rhine and Ringstrasse, were developed as promenades with footpaths, bridleways and, in some cases, cycle paths. Sports facilities for lawn tennis were built at the Blumenwiese and in the Nero Valley. The Tattersall, an indoor riding arena with stables, also for rental horses, was completed in 1905. From there, a bridle path led into the Nero valley and the Taunus forests.

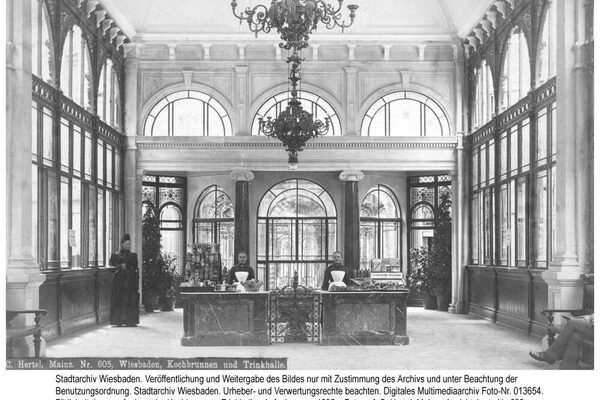

The Medical Department of the Royal Prussian Government promoted the professionalization of spa medicine, which continued to focus on bathing cures. In addition to the emerging drinking cure, the saline thermal baths were also used for inhalation cures. A publication on "Mineral springs and winter stays in Wiesbaden", published in 1875, contributed to the further flourishing of spa life. After this, drinking cures became increasingly important in medicine. However, the prerequisite for an expansion of the drinking cure was the redesign of the Kochbrunnen district through the relocation of the hospital and the construction of a new drinking hall. By 1890, the octagonal spring pavilion that still exists today, a beautiful garden facing Taunusstrasse and a drinking and promenade hall designed by Wiesbaden architect Wilhelm Bogler (1887-90) had been built. With the demolition of the old hospital, the municipal baths for the poor also disappeared. A spa center, the municipal Kaiser-Friedrich-Bad, equipped according to the latest balneological and medical findings, was opened in 1913. The new municipal hospitals were built outside the spa district between Kastellstrasse and Platter Strasse and were occupied on August 16, 1879. Around 1900, Wiesbaden was a city with dense and specialized medical care. The 1910 spa guide lists five public hospitals, 23 private sanatoriums and over 200 doctors, including specialists from all fields, 18 dentists and over 40 masseurs, with gout and rheumatism treatments being of particular importance.

Public health care" was further expanded. Police regulations and ordinances, which had to be observed when selling food and producing milk on farms, served to improve hygienic conditions. Five "milk spas" with their own stables supplied "spa and children's milk". The Fresenius Chemical Laboratory carried out the chemical testing of food samples in accordance with the Imperial Food Law of 1879 on behalf of the state. The Medical Department of the Royal Prussian Government was responsible for combating infectious diseases and the sanitary control of the practice of the healing professions, the sale of remedies, pharmacies, the hygiene of public buildings and places, hospitals and schools, commercial facilities and bathhouses as well as the supervision of prostitution. In 1903, an ambulance station was set up and attached to the fire department. Later, the entire ambulance service was transferred to the professional fire department. Wiesbaden also appeared to be an ideal spa town and residence for the elderly in terms of medical care and urban hygiene. The "Congress for Internal Medicine" was held here for the first time on April 20, 1882(Internists' Congress). In 1891, the Wiesbaden Medical Association characterized Wiesbaden in a memorandum as a "luxury city" in contrast to "factory and trading cities".

The image as a city of healthy living and healing cures, as a refuge for pensioners and retirees, attracted more and more new visitors and residents and at the same time acted as a social selection factor (pupils). It was above all in the villa areas on Sonnenberger Strasse, in the Nero Valley and between Parkstrasse and Frankfurter Strasse that the holders of aristocratic titles, high-ranking officers and civil servants, factory owners, councillors of commerce, directors, bankers and owners of manors lived. But wealthy newcomers also found accommodation befitting their status in Rheinstrasse, Bahnhofstrasse and Kaiser-Friedrich-Ring. The old town, with its stores, craft businesses, inns and hotels, was characterized by a mostly local middle-class residential population. Around 1900, the adjacent Bergkirchen district to the northwest was mainly home to the service staff for the huge spa business, but also to singers, musicians, theater painters and workers, a considerable number of day laborers and many craftsmen.

The entertainment and diversions on offer were primarily aimed at spa guests and wealthy newcomers. The spa guests gathered in the Kochbrunnen drinking and promenade halls from early in the morning. The afternoons and evenings, on the other hand, were devoted to pleasure and entertainment, for which the program in the Kurhaus and spa gardens offered ample opportunity. The close connection between medical and social cures provided psychological relief: medicine legitimized the culture of pleasure and luxury, the morning drinking cure the afternoon and evening amusements (Fuhs). There was a wide range of social events, balls, concerts, theater and sports to keep spa guests and rentiers occupied and entertained. In the afternoons and evenings, the spa orchestra played in the spa gardens or in the Kursaal, depending on the weather. Important artists chose the city as their residence or stayed here for months at a time. Brahms completed his 3rd Symphony in Wiesbaden, which was premiered under his direction in the Kursaal in 1884. Gustav Freytag spent the winter months in Wiesbaden and Friedrich von Bodenstedt gathered a circle of friends around him.

The wide range of physical and sporting activities on offer was groundbreaking. Here, too, the healing, health-promoting aspect was combined with the social aspect. The charming surroundings of the town were transformed into a spa landscape in the course of the 19th century. Walks in the countryside were an integral part of spa life around 1900. Fuhs even speaks of a "sportification of the spa" around 1910, which included horse riding, bicycle tours, rowing trips on the Rhine and on the spa pond, croquet and lawn tennis as well as ice skating and tobogganing in winter. Pistol and rifle shooting were also popular sports. The Wiesbaden Tennis and Hockey Club (WTHC), founded in 1905, organized international tournaments and was sponsored by the spa management and "well-known personalities". Equestrian sport played an important role as an exclusive pastime. The morning "ride", which Kaiser Wilhelm II also enjoyed with his entourage, was part of the social self-presentation. At the racecourse in Erbenheim - as in Baden-Baden - the sophisticated world could present itself. On big race days, 20,000 to 25,000 visitors came. Other sporting attractions included parachuting, ballooning and car racing.

Literature

Bleymehl-Eiler, Martina: Stadt und frühneuzeitlicher Fürstenstaat: Wiesbadens Weg von der Amtsstadt zur Hauptstadt des Fürstentums Nassau-Usingen (Mitte des 16. bis Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts), 2 vols., uned. diss., Mainz 1998.

Bleymehl-Eiler, Martina: The cultivated atmosphere. Wiesbaden in the imperial era. In: Eisenbach, Ulrich et al. (ed.): Reisebilder aus Hessen. Tourism, health resorts and tourism since the 18th century. Hessisches Wirtschaftsarchiv, Schriften zur hessischen Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensgeschichte 5, Darmstadt 2001 [pp. 73-84].

Bleymehl-Eiler, Martina: A small Elysium. The Nassau baths in the 19th century. In: Nassau and its baths in the period around 1840, Wiesbaden 2005 [pp. 69-117].

Fuhs, Burkhard: Mondäne Orte einer vornehmen Gesellschaft, Hildesheim [et al.] 1992.

The public health care of Wiesbaden. Festschrift presented by the city of Wiesbaden. Edited by Rahlson, H[elmut] on behalf of the magistrate, Wiesbaden 1908.

Müller-Werth, Herbert: Geschichte und Kommunalpolitik der Stadt Wiesbaden unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der letzten 150 Jahre, Wiesbaden 1963.