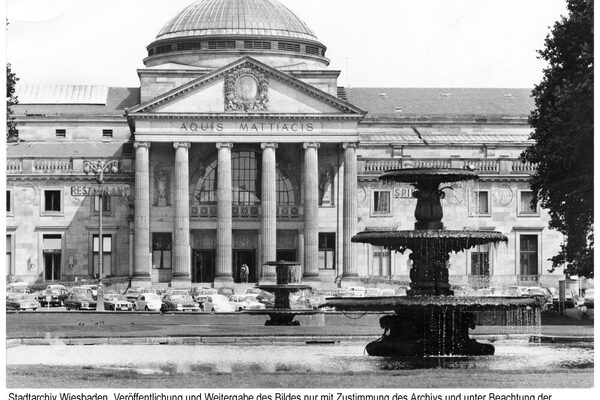

Kurhaus, new

By 1900 at the latest, the old Kurhaus built by Christian Zais was no longer considered up to date. After Felix Genzmer had already submitted initial plans for a new building in 1895, Friedrich von Thiersch was finally commissioned with the planning and construction in 1902. While the intention up to this point was to place the new building behind the old Kurhaus in the park, Thiersch planned to demolish it and build a new one on the same site.

The neoclassical Kurhaus had been included by the provincial curator Ferdinand Luthmer in the "Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler" (monuments of architecture and art) he had compiled for the administrative district of Wiesbaden, meaning that it was a listed building in accordance with Prussian regulations. However, Kaiser Wilhelm II overruled Luthmer's objection to the demolition. Permission for the demolition was granted, but with the condition that two columns and a piece of the portico's architrave be preserved and that the old Kursaal be rebuilt in a new building or in another municipal building. At the end of the process, a compromise was reached and the start of construction was delayed until 1904.

Out of consideration for the protection of historical monuments and the resentment of the citizens, Thiersch chose the classicist style for the design of the exterior and also tried to prove with photomontages that the new building would only be marginally larger than the old building. In reality, the built-up area increased from 4,887 to 6,235 m². Thiersch's reasons for the neoclassical design language were, firstly, consideration for the neoclassical colonnades and, secondly, the memory of Roman Wiesbaden, as expressed in the inscription "AQUIS MATTIACIS" on the portico. The central domed lobby is also inspired by Roman thermal baths. Among other things, Thiersch adopted the Roman tradition of only using natural stone for the lower wall sections of the monumental hall by using dark red Swedish granite for the columns and pilasters, yellow Sienese marble for the dome pillars and green serpentine for the four pedestals in front of the corner pillars. On the latter are marble copies of four ancient statues, the originals of which are in the museums of Dresden, Bologna, Munich and Florence. Athena symbolizes wisdom, Eirene with Pluto peace and wealth, Apollo the arts and Asclepius health, i.e. the prerequisites for the success of the cure.

When designing the interior, Thiersch used several hist. Styles as a model. The magnificent large concert and ballroom, known since 1987 as the Friedrich-von-Thiersch-Saal, is in the neo-baroque style, while the smaller Christian-Zais-Saal opposite, which has been rebuilt using the original columns, has a simple classical appearance due to its sparse decoration. The cherry wood wall paneling of the former wine hall, which now serves as a casino, is designed in the German Renaissance style. The beer hall, which no longer exists, was clad wall-high with glazed tiles. Today it is part of the restaurant. The adjoining Bacchus Room to the north still has the original replica of a late Gothic wooden ceiling with rather hearty sayings in Middle High German. The smaller cabinets around the main hall are decorated in various neo-baroque styles. The shell room on the south side of the Kurhaus was intended as a reading room. The Emperor's wrath was aroused by Fritz Erler's Art Nouveau murals, original and unconventional depictions of the four seasons and the theme of "Youth and Old Age".

Among the buildings of late historicism in Wiesbaden, the Kurhaus stands out not only for its high-quality interior design, but also for the progressiveness of the original technical equipment. These included an ingenious system for ventilating and heating the rooms, water supply via two separate systems for drinking and service water, an ice machine for cooling drinks and food and for producing artificial ice, electric motors for bread-cutting, knife-cleaning and dishwashing machines, four electric elevators and a compressed air purification system with 25 connection points.

The new Kurhaus was also planned as a social, catering and concert venue. During the construction period of the Kurhaus (1905-07), the Paulinenschlösschen served as a temporary Kurhaus. Together with the Kurpark and the Bowling Green, it formed the center of social life in the cosmopolitan spa town of Wiesbaden in the 20th century. Emperors and kings, princes and financial magnates from all over the world strolled here until the beginning of the First World War. Balls, soirées and lavish parties, light entertainment, but also top-class concerts characterized the social life of the imperial era.

In 1908, Gustav Mahler conducted his Symphony No. 1 with the Kurhaus Symphony Orchestra, and in 1912, Brahms fans from all over Germany made a pilgrimage to the Kurhaus for the Brahms Week. From 1912 onwards, conductor Carl Schuricht enhanced the city's musical reputation for 32 years. Famous guest conductors and composers such as Max Reger, Wilhelm Furtwängler and Igor Stravinsky contributed to Wiesbaden's fame as a city of music, which continued even during the years of hardship after the First World War. In the 1920s, Carl Hermann Rauch, theater director and spa director in one, brought famous singers and performers, such as the pianist Elly Ney, and great conductors such as Karl Böhm, Sir Henry Joseph Wood and Wilhelm Mengelberg to Wiesbaden.

The Kurhaus was opened with a pompous celebration in the presence of Emperor Wilhelm II on 11.5.1907. Together with his wife Auguste Viktoria, he took a seat in his imperial box. The Wiesbaden goldsmiths had made a gold goblet especially for this day, from which the Emperor took his drink of honor. The goblet now stands in a display case in the foyer of the new town hall.

The Bowling Green was also a parade ground for military parades. On January 27, the Kaiser's birthday, the Fusilier Regiment von Gersdorff, stationed in Wiesbaden, traditionally paraded here. In 1918-25, the French demonstrated their power here with their tanks, followed by the British in 1925-30. The National Socialists also seized the Kurhaus after 30.01.1933. Hitler's birthday was celebrated every year with a symphony concert, and the anniversary of the march on Munich's Feldherrenhalle was known as the "Good Friday of National Socialism". The Volkssturm, the last contingent of the lost war, also gathered on the Bowling Green.

During the major bombing raid on the night of February 3, 1945 by the Royal Air Force, the south wing of the Kurhaus with the large concert hall was destroyed. The Americans seized the north wing and set up their Eagle Club there. Artists flown in from the USA shone here, one of the most famous being Frank Sinatra.

The south wing remained a ruin until 1951. Its reconstruction in simpler forms was seen by contemporaries as a symbol of Wiesbaden's will to rebuild. In 1959, the Kurhaus audience lay at the feet of Maria Callas. In 1963, the city cheered the American President John F. Kennedy, who drove to the Kurhaus with Vice Chancellor Ludwig Erhard and Prime Minister Georg August Zinn in an open car along Wilhelmstrasse. In 1965, the British Queen Elizabeth II and her husband Prince Philip were given an enthusiastic reception here. The list of prominent state guests continues with Mikhail Gorbachev and Russia's President Vladimir Putin, who both visited Wiesbaden in 2007 on the occasion of the Petersburg Dialogue.

In 1982-87, the Kurhaus was restored in several construction phases on the basis of the preserved original plans by Friedrich von Thiersch. Since then, the building has enjoyed a new lease of life as a concert, festival and congress venue. The "Three Tenors", José Carreras, Plácido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti, have shone in open-air performances here. Pop culture greats such as Sting, Bryan Adams and Elton John have also performed here.

In 2006, just in time for the 100th anniversary in 2007, the new underground parking garage was completed. There had previously been fierce disputes about its construction, or more precisely about the felling of the old plane trees from the 19th century.

Wiesbaden's casino has been back in the Kurhaus since 1955 It had previously been located in the old Kurhaus until gambling was banned in the German Reich in 1872. In 1949-55, it was located in the foyer of the Hessian State Theater in Wiesbaden.

Literature

Gerber, Manfred: The Wiesbaden Kurhaus. Kaleidoscope of a century, Bonn 2007.

Kiesow, Gottfried: Architectural Guide Wiesbaden. The City of Historicism, Bonn 2006 [pp. 14-23].