Roman times

The Roman city of Wiesbaden is mentioned several times in literary sources. Pliny the Elder emphasizes the importance of its thermal springs, while the poet Martial mentions the Mattiac balls in his epigrams, which were supposed to prevent hair loss. The historian Tacitus also makes several references to the Chatti and the Mattiacs who gave the area its name. In the most important work on ancient geography, the Geographike Hyphegesis, the geographer Klaudios Ptolemaios deals with Germania Megale (Greater Germania, i.e. Free Germania on the right bank of the Rhine). Among others, the Chatti tribe settled there, of which the Mattiacs are considered a sub-tribe. The Rhine-Main region, the old route of entry and transit from north to south, was controlled by the Romans around the turn of the millennium and thus at an early stage. Nevertheless, the date of the founding of a military post in Wiesbaden remains uncertain to this day, even though military finds from the Augustan period from the so-called moor layer have been discovered. This 0.50 - 1.5 m thick layer, found between Kirchgasse and Langgasse, contained the earliest finds dating from the time of Agrippa to Domitian and therefore marks the oldest settlement area of the new town founded by the Romans ("vicus"). The continuous development was disrupted in 69/70 AD when the Mattiacs, Chatti and Usipetes besieged Mainz and the finds from the bog layer came to an abrupt end.

In the early 2nd century, Wiesbaden became the suburb of the administrative unit "civitas Ulpia Mattiacorum", which was probably founded during the reign of Traian. From here, a magistrate together with the decurion council administered the area between the Schwarzbach in the east, the Main and Rhine in the south and the Limes in the north, following the Roman model. Only in the west does the boundary of the territorial authority remain unknown. Members of this council are known from inscriptions from Wiesbaden, Mainz-Kastel and Mainz. Even if the settlement never received a higher legal status, the administration located here presupposes public buildings such as a forum with an adjoining basilica, which have not yet been found in Wiesbaden. The settlement also lacks the walled enclosure found in other civitas suburbs.

The Alamanni invasions in 260 AD took a heavy toll on the "vicus", as both the size of the settlement and the population appear to have been significantly decimated. Despite this, the settlement continued to exist into the 4th century. The main reason for this was probably the spa business. Under Emperor Valentinian, a new type of defensive concept was developed to secure the imperial border on the Rhine. Observation posts were stationed on the right bank of the Rhine in small, solidly built forts ("burgi") with a landing stage. One of these posts was also located in Wiesbaden-Schierstein. The construction of the Heidenmauer parallel to a road running through the "vicus" also belongs in the context of these protective measures. The invasion of the Quads, Alands and Vandals in January 406 AD probably marked the end of settlement activity. The military occupation of Wiesbaden has been documented since Claudian times, which ended in the early 2nd century with the withdrawal of the cohort stationed here.

Civilian settlement developed parallel to the expansion of the military facilities on the Heidenberg. The approximately 25-hectare "vicus", which stretched between Schwalbacher Strasse, Friedrichstrasse and Wilhelmstrasse, was primarily important as a spa for the soldiers of the Mainz legions. This is shown not only by the resumption of bathing activities in the Constantinian period, when the previously lost area on the right bank of the Rhine was reoccupied, at least near the shore, but also by the numerous soldiers' gravestones of veterans from various units. To this day, no clear street grid can be identified in the oval settlement area measuring around 700 x 450 m. However, a route corresponding to the modern Langgasse, the remains of which have been observed several times, was probably one of the main streets, especially as the large thermal baths were also aligned along its course. No less important is a second street, towards which the buildings examined in today's Schützenhof area are oriented and which lay diagonally to the others. It probably continued in an easterly direction towards Hofheim. Of the three large thermal bath buildings, those on Langgasse next to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Therme and in the area of the Schützenhof could only be partially examined, but not completely. The thermal baths at the Schützenhof were supported by the troops stationed in Mainz between 70 and 92 AD due to the use of lead pipes from legio XIV Gemina Martia Victrix, but this does not confirm their use as garrison baths for the fort on the Heidenberg. Only the baths near the Kochbrunnen on Kranzplatz with a supposedly neighboring lodging house ("mansio") could be examined more comprehensively by Emil Ritterling in 1903, although no excavation report was published. Between the late 1st and 4th centuries, the 1st, 8th, 14th and 21st legions from Mainz, whose members made intensive use of the healing springs, were involved in its construction. In addition to the usual bathing pools with water at different temperatures, there were also small bathing niches especially for the healiWilhelmstrasse, was primarily important as a spa for the soldiers of the Mainz legions. This is shown not only by the resumption of bathing activities in the Constantinian period, when the previously lost area on the right bank of the Rhine was reoccupied, at least near the shore, but also by the numerous soldiers' gravestones of veterans from various units. To this day, no clear street grid can be identified in the oval settlement area measuring around 700 x 450 m. However, a route corresponding to the modern Langgasse, the remains of which have been observed several times, was probably one of the main streets, especially as the large thermal baths were also aligned along its course. No less important is a second street, towards which the buildings examined in today's Schützenhof area are oriented and which lay diagonally to the others. It probably continued in an easterly direction towards Hofheim. Of the three large thermal bath buildings, those on Langgasse next to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Therme and in the area of the Schützenhof could only be partially examined, but not completely. The thermal baths at the Schützenhof were supported by the troops stationed in Mainz between 70 and 92 AD due to the use of lead pipes from legio XIV Gemina Martia Victrix, but this does not confirm their use as garrison baths for the fort on the Heidenberg. Only the baths near the Kochbrunnen on Kranzplatz with a supposedly neighboring lodging house ("mansio") could be examined more comprehensively by Emil Ritterling in 1903, although no excavation report was published. Between the late 1st and 4th centuries, the 1st, 8th, 14th and 21st legions from Mainz, whose members made intensive use of the healing springs, were involved in its construction. In addition to the usual bathing pools with water at different temperatures, there were also small bathing niches especially for the healing and spa facilities, which could be uncovered on the east side of one of the four large pools.

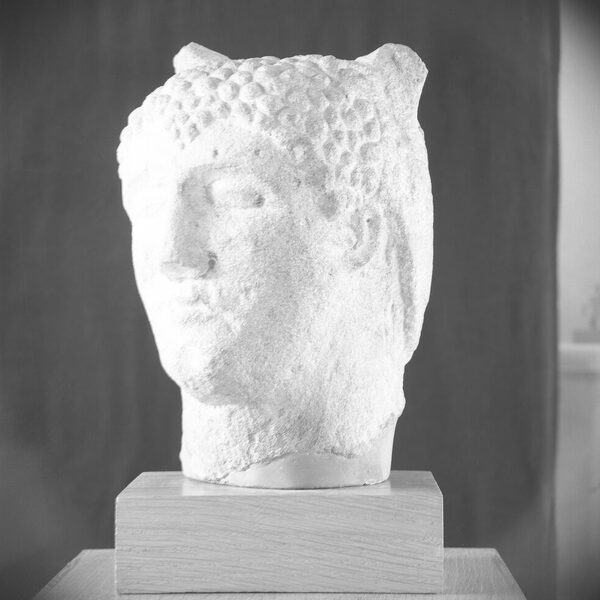

Little is known about the remaining buildings of the Roman "vicus". A temple to Iupiter Dolichenus may have stood in the Adlerterrain, according to a dedicatory stone from 194 AD. Other public buildings are thought to have stood on Langgasse. An inscription plate found on the north side of Mauritiusplatz proves the existence of a previously unlocated merchants' guild house. The Mithraeum on Coulinstraße has also been investigated In the suburb of the local authority, more extensive residential buildings ("domus") would also be expected, in which the members of the elite lived. So far there is no evidence of this. In addition, there were certainly simpler half-timbered buildings, which, like the later stone architecture, must have been founded on pile grids, at least in the wetland area between Hochstädtenstrasse and Mauritiusstrasse. The cemeteries marking the end of the settlement area were cut along Schwalbacher Straße and between Luisenstraße and Rheinstraße on the site of the former artillery barracks. Burials took place continuously until the early Christian period, as numerous grave slabs such as that of Q(u)alaq(u)it testify to the existence of an early Christian community in the settlement. In the middle of the 4th century, the renewed use of the thermal baths by the military promoted a second heyday of the settlement. The protective measures initiated by Valentinian I included not only the construction of "burgi" but also the building of the Pagan Wall, which was never completed. In addition to the soldiers' gravestones built into the wall, a statue from the nearby Mithraeum is the main evidence for its dating to this late period.

The population of the vicus must have consisted of immigrant, more or less Romanized Gauls and other members of the empire in addition to the native Mattiacs and Romans. According to the names ("tria nomina") that have been handed down, some of them probably had Latin citizenship. Known by name are the native V. Lupulus, who allowed a Mithras congregation to build a temple on his land, and Agricola, a pottery dealer probably from Gaul, for whom his daughter had a carefully crafted and therefore certainly expensive gravestone erected.

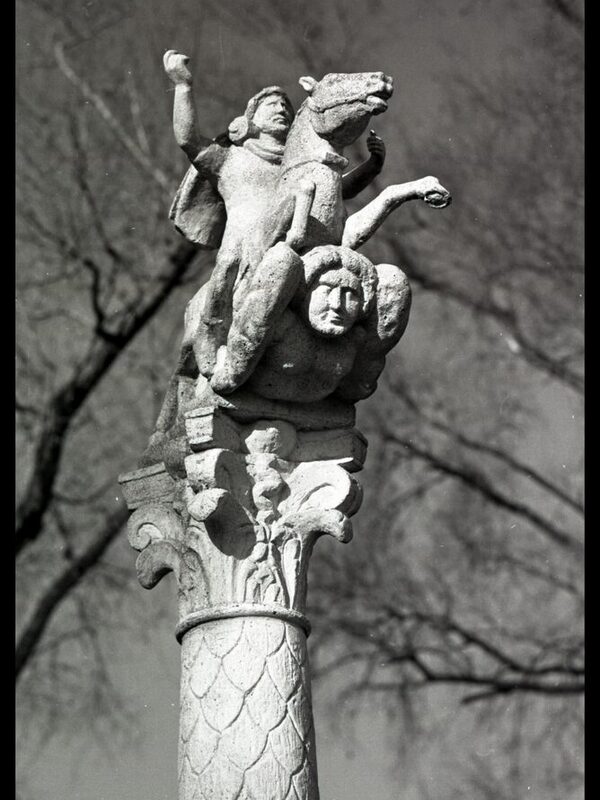

The emperor's priest was the lawyer ("pragmaticus") C. Iulius Simplicius, whose tombstone was installed in the Mainz citadel. Colleges of priests ("Augustales") led the imperial cult, which was not dedicated to a god-like emperor, but to the divine work ("numen") of the emperor as the force that ensured the protection of the state through its connection to the gods. Even if the exact location of the rebuilt Sirona temple remains unknown, there must have been numerous sanctuaries in Wiesbaden in which Roman and local gods with similar characteristics were linked and worshipped together. For example, Diana "Mattiaca" was probably regarded as the protector of the healing springs just as much as Apollo Toutiorix, while the Celtic horse goddess Epona also enjoyed great popularity among the Romans without a corresponding equivalent. Cults from the Near East, such as that of Mithras or Iupiter Dolichenus, were apparently particularly attractive. Smaller figurines of gods with the entire pantheon probably came from the altars of private households.

Numerous "villae rusticae" were found in the vicinity of the "vicus", similar to today's outlying farmsteads, whose owners farmed and sold their surplus produce on the city market. Examples include the complexes on the Neroberg, the Wellritzmühle, the Gräselberg, the Adolfshöhe, the Landgraben near Mosbach, Bierstadt, Igstadt and Breckenheim. Unfortunately, none of the estates have been comprehensively investigated. The interpretation of a small "settlement" on Hollerborn near Dotzheim also remains unclear. Its loosely scattered buildings are said to have stretched for "over a quarter of an hour" in the direction of Wiesbaden.

According to the three preserved milestones set in 122 and 235/38 AD and in the middle of the 3rd century, Wiesbaden was integrated into an extensive road network, even if it never formed an important transportation hub due to its peripheral location in the province. The most important route to Mainz-Kastel ran from the right side gate ("porta principalis dextra") of the fort, after a slight bend, straight down the Heidenberg and across Mauritiusstrasse and Faulbrunnenstrasse to join up with today's Moritzstrasse between Albrechtstrasse and Adelheidstrasse. The 5.30 m wide, centrally arched road was paved with large, irregular slabs and was probably built on a raised embankment with a pile grid substructure in the marshy area between Mauritiusstrasse and Faulbrunnenstrasse. This route, which was developed at the same time as the fort, met the large road leading from Mainz via Nida-Heddernheim into the Wetterau 50 m north of the Mainz-Kastel bridgehead fort. The two milestones set at this junction indicate the distance from Wiesbaden (from Mattiacorum) almost exactly at 9 km in the different units of measurement of the Roman foot or the "leuge" art form developed in Gaul. A second route, which was probably already used in pre-Roman times, led to Hofheim. It began at the main gate ("porta praetoria") and could be observed on the Dern site, in De-Laspée-Straße and in the courtyard of the Wiesbaden Museum. Its course was also accompanied by the Heidenmauer in the central vicus area. A road may have led from the left side gate ("porta principalis sinistra") to the Limes fortifications in the Taunus, which probably ended at Fort Heidekringen. The posts of a small road station on the rent wall are said to have controlled traffic on this road leading to the border. In contrast, the route leading west into the Rheingau, whichRheinstraße on the site of the former artillery barracks. Burials took place continuously until the early Christian period, as numerous grave slabs such as that of Q(u)alaq(u)it testify to the existence of an early Christian community in the settlement. In the middle of the 4th century, the renewed use of the thermal baths by the military promoted a second heyday of the settlement. The protective measures initiated by Valentinian I included not only the construction of "burgi" but also the building of the Pagan Wall, which was never completed. In addition to the soldiers' gravestones built into the wall, a statue from the nearby Mithraeum is the main evidence for its dating to this late period.

The population of the vicus must have consisted of immigrant, more or less Romanized Gauls and other members of the empire in addition to the native Mattiacs and Romans. According to the names ("tria nomina") that have been handed down, some of them probably had Latin citizenship. Known by name are the native V. Lupulus, who allowed a Mithras congregation to build a temple on his land, and Agricola, a pottery dealer probably from Gaul, for whom his daughter had a carefully crafted and therefore certainly expensive gravestone erected.

The emperor's priest was the lawyer ("pragmaticus") C. Iulius Simplicius, whose tombstone was installed in the Mainz citadel. Colleges of priests ("Augustales") led the imperial cult, which was not dedicated to a god-like emperor, but to the divine work ("numen") of the emperor as the force that ensured the protection of the state through its connection to the gods. Even if the exact location of the rebuilt Sirona temple remains unknown, there must have been numerous sanctuaries in Wiesbaden in which Roman and local gods with similar characteristics were linked and worshipped together. For example, Diana "Mattiaca" was probably regarded as the protector of the healing springs just as much as Apollo Toutiorix, while the Celtic horse goddess Epona also enjoyed great popularity among the Romans without a corresponding equivalent. Cults from the Near East, such as that of Mithras or Iupiter Dolichenus, were apparently particularly attractive. Smaller figurines of gods with the entire pantheon probably came from the altars of private households.

Numerous "villae rusticae" were found in the vicinity of the "vicus", similar to today's outlying farmsteads, whose owners farmed and sold their surplus produce on the city market. Examples include the complexes on the Neroberg, the Wellritzmühle, the Gräselberg, the Adolfshöhe, the Landgraben near Mosbach, Bierstadt, Igstadt and Breckenheim. Unfortunately, none of the estates have been comprehensively investigated. The interpretation of a small "settlement" on Hollerborn near Dotzheim also remains unclear. Its loosely scattered buildings are said to have stretched for "over a quarter of an hour" in the direction of Wiesbaden.

According to the three preserved milestones set in 122 and 235/38 AD and in the middle of the 3rd century, Wiesbaden was integrated into an extensive road network, even if it never formed an important transportation hub due to its peripheral location in the province. The most important route to Mainz-Kastel ran from the right side gate ("porta principalis dextra") of the fort, after a slight bend, straight down the Heidenberg and across Mauritiusstrasse and Faulbrunnenstrasse to join up with today's Moritzstrasse between Albrechtstrasse and Adelheidstrasse. The 5.30 m wide, centrally arched road was paved with large, irregular slabs and was probably built on a raised embankment with a pile grid substructure in the marshy area between Mauritiusstrasse and Faulbrunnenstrasse. This route, which was developed at the same time as the fort, met the large road leading from Mainz via Nida-Heddernheim into the Wetterau 50 m north of the Mainz-Kastel bridgehead fort. The two milestones set at this junction indicate the distance from Wiesbaden (from Mattiacorum) almost exactly at 9 km in the different units of measurement of the Roman foot or the "leuge" art form developed in Gaul. A second route, which was probably already used in pre-Roman times, led to Hofheim. It began at the main gate ("porta praetoria") and could be observed on the Dern site, in De-Laspée-Straße and in the courtyard of the Wiesbaden Museum. Its course was also accompanied by the Heidenmauer in the central vicus area. A road may have led from the left side gate ("porta principalis sinistra") to the Limes fortifications in the Taunus, which probably ended at Fort Heidekringen. The posts of a small road station on the rent wall are said to have controlled traffic on this road leading to the border. In contrast, the route leading west into the Rheingau, which probably overlapped in places with the "Sterzelpfad", remained of only minor importance.

Literature

Article Mattiacum. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 19, 2nd ed., Berlin, New York 2001 [p. 440 ff.].

Czysz, Walter: Wiesbaden in der Römerzeit, Stuttgart 1994.