Persecution, expulsion and murder of Jews in Wiesbaden from 1933-1945

Over 3,000 Jews lived in Wiesbaden towards the end of the Weimar Republic. In 1933, the NSDAP initially set about separating Jews from the rest of the population and isolating them socially. The first large-scale anti-Jewish campaign began on April 1, 1933 with the boycott of Jewish businesses, doctors and lawyers staged by the NSDAP. Signs with the inscription "Don't buy from Jews" were placed in front of numerous stores in Wiesbaden.

The hatred of Jews, which was increasingly fueled by party propaganda and in Wiesbaden even before 1933 by the "Nassauer Beobachter" (later "Nassauer Volksblatt"), a newspaper in the style of the "Stürmer", led to abuse and murder early on: On March 27, 1933, the owner of the "1st Silk Shop in Wiesbaden, Wilhelmstraße 20" Salomon Rosenstrauch was attacked and abused by the SA. During a second attack in his store on 22.04.1933, he suffered a fatal heart attack. On the same day, the milk merchant Max Kassel was shot in the back and killed in his apartment at Webergasse 13. The brutal murders, which were still reported in Wiesbaden's daily newspapers in 1933, albeit in a veiled manner, moved on to the quieter phase of the dismissal of Jews (and political opponents) from the civil service on the basis of the "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service" of April 7, 1933.

Anti-Semitism also had an impact on schools. Alfred Milmann, who attended the secondary school on the Riederberg, reported that Jewish pupils had already been separated from the other pupils in 1934. Until his emigration with his parents, Alfred Milmann then attended the Jewish elementary school in Wiesbaden, which was set up in barracks in Mainzer Straße in 1936. The exclusion of Jewish youths had already taken place step by step through the exclusion from "German" clubs (Gleichschaltung) and the banning of non-Zionist youth groups and Jewish sports clubs. Zionist organizations, however, which were oriented towards emigration to Palestine and had increasing popularity, were allowed to continue to operate in the non-public sphere. Only the youth section of the Reich Association of Jewish Frontline Soldiers was granted a special permit for sports activities.

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 deprived all Jews of their civil rights and prohibited marriages between Jews and so-called Aryans. Even the employment of "Aryan" domestic servants could lead to imprisonment in a concentration camp for both parties. The Nuremberg "Reich Citizenship and Blood Protection Act", co-formulated by Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart from Wiesbaden, provided the "legal" basis for the process of exclusion and persecution. Not only large companies such as IG Farben or Dresdner Bank profited from forced labour or aryanization, but also small Wiesbaden companies or the city administration, which employed Jews for road work. The largest share of aryanized assets was confiscated by the tax office, but a considerable proportion went to ordinary citizens of the Reich, often via the Nazi welfare service.

In 1937, forced aryanization became the main thrust of anti-Jewish measures - above all to force Jews to emigrate. In 1938, new laws and ordinances were also constantly being passed to destroy any remaining economic activity by Jews. The Wiesbaden-based company Steinberger & Vorsanger initially suffered heavy losses as a result of the boycott measures. On 07.03.1938, the company was aryanized. The consequence of the expropriations was a rapid impoverishment of the Jewish population. At the same time, the Wiesbaden SA continued its violent actions. The increasing destitution made emigration more and more difficult for the majority of Jewish families, and fewer and fewer countries accepted Jews and closed their borders.

Wiesbaden's synagogue on Michelsberg was completely burnt down during the so-called Reichskristallnacht, and the interior of the Old Israelite Synagogue in Friedrichstraße was desecrated. Jewish businesses were also vandalized. Almost all Jewish men were arrested on the night of the pogrom, including the retired Wiesbaden rabbi Dr. Paul Lazarus and, like the "legal advisor" Dr. Guthmann, who had been appointed to represent the Jews, were interned for several months in Buchenwald concentration camp. In the suburbs of Biebrich and Schierstein, the destruction of the synagogues was followed by brutal attacks on private homes. The expropriations were celebrated as the "de-Jewification of the economy" and were largely completed when the final phase of persecution began in 1941.

The phase of extermination began with the first major deportations. The majority of the German population was largely absorbed by the war; the sudden disappearance of entire families in the neighbourhood, who were initially ghettoized in so-called Jewish houses, was accepted without protest. From September 1, 1941, all Jews had to wear a yellow star on their clothing. Anyone who did not wear it visibly, concealed their forced first name Sara or Israel or violated one of the many Jewish ordinances, such as the ban on entering the spa gardens or keeping pets, and was denounced, was threatened with being sent to a concentration camp.

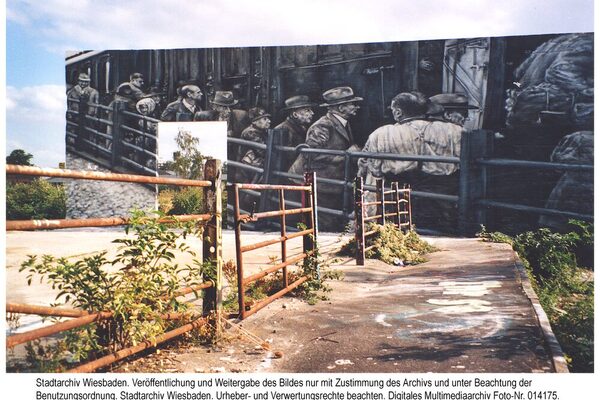

In January 1942, around 1,000 Jewish men and women were still living in Wiesbaden. About the same number had emigrated and a few had managed to flee illegally across the border. Almost all those who stayed behind were deported to the extermination camps in three large deportations in March, June and September 1942 from the slaughterhouse ramp at the main railway station. On June 10, 1942, families from Wiesbaden in particular were deported to Sobibor or Majdanek. "Evacuated to the East" was written on the Gestapo's index cards, with which they meticulously tried to register every Jew in the city. This deportation hit the Jewish community at its core; entire families were deliberately put on the deportation list. Those left behind were mainly older people and Jews who were married in a so-called mixed marriage, or front-line soldiers who had fought for Germany in the First World War. Before the last major deportation on September 1, 1942, 40 men and women of Jewish origin took their own lives. In March 1945, when Auschwitz had already been liberated, a group of so-called mixed-blood children from Wiesbaden were deported to Theresienstadt with their Jewish parents.

The number of Holocaust victims from Wiesbaden, i.e. Jews who were deported from Wiesbaden or born in Wiesbaden but deported from another German or foreign city and murdered in an extermination camp, including those who committed suicide due to persecution or imminent deportation, is at least 1,500 people - including at least 120 Jewish children and young people.

Literature

Aly, Götz: Hitler's People's State. Raub, Rassenkrieg und nationaler Sozialismus, Frankfurt am Main 2005.

Bembenek, Lothar/Ulrich, Axel: Resistance and Persecution in Wiesbaden 1933-1945. A Documentation. Ed.: Magistrat der Landeshauptstadt Wiesbaden - Stadtarchiv, Gießen 1990.

Bembenek, Lothar/Dickel, Horst: I am no longer a German patriot, now I am a Jew. The expulsion of Jewish citizens from Wiesbaden from 1933 to 1947, Wiesbaden 1991.

Bembenek, Lothar: Political criminals. SA murders of Wiesbaden citizens (1933). In: Fuchs, Crimes and Fates [pp. 99-112].