Large housing estates

In the 1960s and 1970s, three large housing estates were built in Wiesbaden based on plans by architect and urban planner Ernst May. The Biebrich-Parkfeld, Klarenthal and Schelmengraben estates were built far from the city center "on greenfield sites". In contrast, the existing old buildings in the city center were often considered unattractive and too expensive to renovate.

Large housing estates were the dominant type of housing construction in the 1960s. There are many reasons for this. The very strong 1960s and 1970s, both economically and in terms of the birth rate, resulted in a correspondingly high demand for housing. In Hesse in 1956, there was still a shortfall of 20.3% in relation to the existing housing stock. In Wiesbaden, it was also expected that the "increasing overcrowding in the Frankfurt area (...) would continue to affect Wiesbaden's appeal as a residential city in the future."

However, the existing building fabric was considered outdated and in need of refurbishment due to the increased requirements in terms of living space, comfort, transport links, location and infrastructure following the completion of the reconstruction. However, refurbishment seemed unattractive due to the "non-profitable costs" that would be incurred. At the same time, the core cities were designated as business and administrative centers, meaning that there was far too little free space for new buildings. At the end of the 1950s, large housing estates of previously unknown dimensions were therefore increasingly built on greenfield sites on the outskirts of the city in order to meet the requirements.

The estates reflected the increasing mobilization of the population: they usually offered very good connections to the freeway, a generously developed road network and sufficient car parking spaces. The separation of pedestrian and motorized traffic was also typical. In terms of floor plans, the focus was on minimizing circulation areas, which often led to solutions with open-plan living rooms, kitchenettes and/or dining areas. Private open spaces in the form of balconies and loggias in almost all apartments offered additional living comfort.

These general developments outlined here were also evident in Wiesbaden. The inner city location of the state capital, in particular the area known as City East, was largely earmarked for the settlement of private and state administrations. The "highly inadequate condition of the old buildings" was to be tackled after the construction of new large housing estates by redeveloping areas, i.e. large-scale demolition.

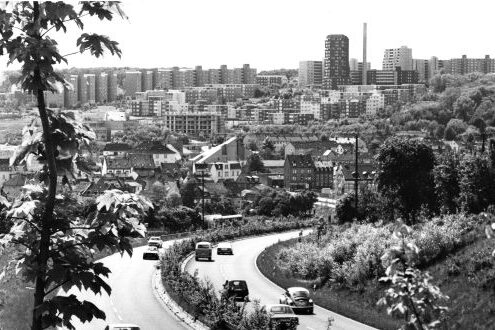

In the 1960s, three large housing estates were built on open land: Biebrich-Parkfeld(Biebrich), Klarenthal and Schelmengraben. The Klarenthal and Schelmengraben housing estates were selected following extensive investigations into air pollution in the urban district. Particularly low levels of pollution had been found at the later settlement sites and the scenic Taunus slopes sloping down into the urban area were also considered to be particularly suitable for residential purposes. The residential areas designated at the time were calculated to be sufficient for a period of around 20 years to accommodate the calculated optimum additional demand for housing.

The large housing estates were built according to the plans of the internationally renowned and experienced architect and urban planner Ernst May. The Biebrich-Parkfeld estate was preceded by a competition, which May had won. May had already developed Klarenthal and Schelmengraben as the city's planning commissioner. The principle of "staggered construction" was applied almost throughout. This involves the deliberate use of different building forms within certain settlement districts: from ground-floor atrium houses to two-storey terraced houses and three- to four-storey mid-rise buildings to high-rise point blocks. The different forms had the function of creating a living environment that was as varied as possible. In some towns and cities, residential rings and lines were also used. In order to avoid urban sprawl on the outskirts of the city and the adjacent open spaces of the city of Wiesbaden, the planners already pointed out that construction in the coming development periods should be concentrated on the designated new settlement areas.

The Biebrich-Parkfeld housing estate, 1959-1970

In 1959, a competition was announced for the Biebrich-Parkfeld housing estate, in which Ernst May was invited to take part by the Wiesbaden city planning officer Simon. Simon was familiar with May's design for the "Am Limes" housing estate in Schwalbach, which had impressed him greatly. A total of 45 designs were submitted for the competition. Ernst May was unanimously awarded first prize. According to May's design, two parallel streets were used to develop the 31.8-hectare site, which sloped from north to south. The street Am Parkfeld already existed and was now separated in its middle section to reduce through traffic. To the west, the continuous Albert-Schweitzer-Allee was added. Together they served as "residential collector streets", i.e. the traffic of the estate was to be collected here, whereas the narrower streets stretched between them like ladders only had to accommodate the direct traffic of residents.

The building types used reflect the desire for a varied architectural landscape with different heights and layouts. The buildings along the three parallel streets running from west to east were initially designed relatively uniformly: Ensembles of blocks of apartment buildings were juxtaposed with terraced houses of different designs. The impression of long, monotonous rows was avoided by the different arrangement to the street and an angular widening of the residential street to accommodate recessed parking spaces and garages. At the same time, the higher blocks to the west each closed off the three residential units visually and acoustically from the thoroughfare. To the north of the center, the residential density increased compared to the southern area, while terraced house complexes formed their own ensembles to the west of the thoroughfare. In the northern area, a supply center with a high-rise building was concentrated, visible from afar. The supply options there were supplemented by schools and a church in the western part of the estate.

The greening of the estate is striking. The site of a former nursery and an extension of the Biebrich Palace Park resulted in spacious green areas, some of which are now used as allotment gardens, while others provide a varied recreational area with a pond and stream. In addition to its function as a dust filter, Ernst May saw the palace park as a welcome recreational area close to residential areas. He also considered the location of the estate in relation to the neighboring commercial and industrial area to be favorable, as this meant that no significant traffic congestion was to be expected.

In the Biebrich-Parkfeld estate, the effort to create humanly comprehensible urban spaces by delimiting manageable residential groups and ensembles is clearly noticeable. They are clearly structured, yet rich in variety. Different types of housing also served to mix the population structure, although this was not always achieved as the estate progressed.

Construction of the estate did not begin until the early 1970s due to protracted land negotiations in a slightly different form to the design. Immediately after Ernst May's success in the competition was announced, he was appointed planning commissioner for the city of Wiesbaden. In this role, he also planned the Klarenthal and Schelmengraben estates.

The Klarenthal housing estate, 1960-1969

With 4,000 new apartments for around 14,000 people on 138.5 hectares, Klarenthal was May's largest closed housing project in Wiesbaden at the time. The settlement is located on a slope that slopes from west to east and is intersected by a ditch. The development was also carried out along this ditch by various collector roads in the form of loops and cul-de-sacs. Two of the roads mainly provide access to terraced houses in the western part of the estate and a single-family house area in the lower-lying eastern part of the estate. A loop in the eastern area provides access to a group of taller buildings with five high-rise buildings with up to 16 storeys at the highest point.

The large housing estate was given its own infrastructure with a shopping center, kindergartens, school and sports facilities. The main center of the estate was located at the intersection of the major roads in the valley. In general, the Klarenthal estate followed the principle of separating living and working areas, which had been demanded since the 1920s. However, 40 years later, the high price of land led to a densification that was expressed structurally in the preference for high-rise buildings. However, the impression of "visual density" was to be avoided by, among other things, the strong greening. The terracing of the buildings and their staggered heights allowed a large proportion of the residents a wide, unobstructed view of the valley and slope.

Automobile and pedestrian traffic was structurally separated. May hoped that the majority of commuter traffic would be handled by public transport, but also foresaw a great need for garages and parking spaces. He therefore planned one garage or parking space per detached house or rental apartment. Two-storey parking garages took advantage of the hillside location. However, the main access road to the estate from Klarenthaler Strasse via Goerdelerstrasse was not built until much later, which contributed to the isolation of the estate for a long time.

Due to both legal requirements and socio-political considerations, the housing, house and property types were also mixed in Klarenthal. The planners here experimented with large panel construction even more than in Biebrich-Parkfeld. Ernst May had already gained experience with this technique in various estates in Frankfurt during the 1920s and was now increasingly using it. The units, produced according to type designs, were assembled into four to eight-storey houses, giving them a characteristic cubic silhouette with flat roofs. The individual elements arrived on site with pipes, door and window frames and heating systems integrated into the ceiling panels. For the outer skin, "absolute practicality with full consideration of the aesthetic requirements was to be the determining factor in the choice of materials. Any borrowed representation (should) be banned". The joints were left visible, so the progressive construction method remained recognizable. However, the aesthetic appearance of the buildings met with strong disapproval from the residents; they were perceived as too monotonous. To mitigate this, a color concept was developed and implemented.

The Schelmengraben housing estate, 1961

The Schelmengraben housing estate, with around 2,400 residential units on 49.2 hectares, is located on a slope adjacent to the Dotzheim district. It was clearly demarcated from the residential areas, with permanent green spaces and a sports center forming the north-eastern edge and a bypass road to the south. A ditch running through the settlement area forms the main access to the settlement. The beginning of the settlement was formed by high-rise point buildings, deliberately used as urban planning dominants. Along the moat, the street is mainly accompanied by mid-rise buildings with eight storeys, some of which are offset or angled. To the east, four-storey buildings were placed along the street like a comb, until single-storey L-shaped buildings form the end in the south. Three further high-rise buildings were placed at the end against the backdrop of the Taunus.

To provide for the residents, the settlement was given a main center, which was located roughly in the middle of the settlement. Shopping facilities, schools and other infrastructure facilities were located here. The planners emphasized that great importance was attached to good ventilation of the adjacent "Märchenland" development and a good view to the east. The construction of the medium-height buildings on supports was intended to serve this purpose. As in Klarenthal, the residents' unobstructed view was also praised as a particular advantage. Here, the ridge overlooks the town in the lowlands and the Rhine valley. The apartments were each allocated a garage and half a parking space, some of which were located in two-storey garages.

The efforts to achieve social integration through mixed housing and ownership forms with structural and stylistic unity, which can be seen in the large housing estates, were still based in the 1920s. Thanks to the social infrastructure facilities that were also planned, social hotspots only developed to a limited extent - in contrast to the pure "dormitory towns" of the 1970s. However, the estates of this period had to contend with the problem of a poor image more than the earlier estates. Initially planned for the middle class, some of them mutated into deportation neighborhoods for socially disadvantaged sections of the population. Some estates still suffer from a rather isolated location today. Of the three estates in Wiesbaden mentioned above, some of these problems can be observed in Schelmengraben in particular.

Literature

- Magistrat der Landeshauptstadt Wiesbaden

The new Wiesbaden. Urban development is not a state, but a process, Wiesbaden 1963.

- Seidel, Florian

Ernst May. Urban planning and architecture in the years 1954-1970 (dissertation), Munich 2008.