Wiesbaden under Nassau rule

The family of the Counts of Nassau goes back to the Counts of Laurenburg and was related to the noble families of the Lahn and Westerwald regions. In the 12th century, the focus of their rule was on the middle Lahn, where the Laurenburgs built Nassau Castle soon after 1100. The Nassau family rose rapidly during the Staufer period, when they excelled in imperial service. Ultimately, they probably owed their enfeoffment with imperial estates in the Wiesbaden area during the 12th and 13th centuries to their proximity to the king. In a first major division in 1255, Count Walram received the property south of the Lahn, while Count Otto received lands north of the river. The partition treaty is silent on Wiesbaden, but the Walram line seems to have been in possession of the town since the seventies of the 13th century. In 1292, Count Adolf, who was elected king in the same year, referred to Wiesbaden as "oppidum nostrum" (our city).

In fact, Wiesbaden had been under Nassau sovereignty ever since and acted as a certain outpost in the Middle Ages against the territorial claims of its neighbors, above all the Lords of Eppstein and the Archbishopric of Mainz. This also becomes clear from the foundation of Klarenthal Monastery by Count Adolf in 1298, which became the house monastery and burial place of some of the counts from the Walram branch.

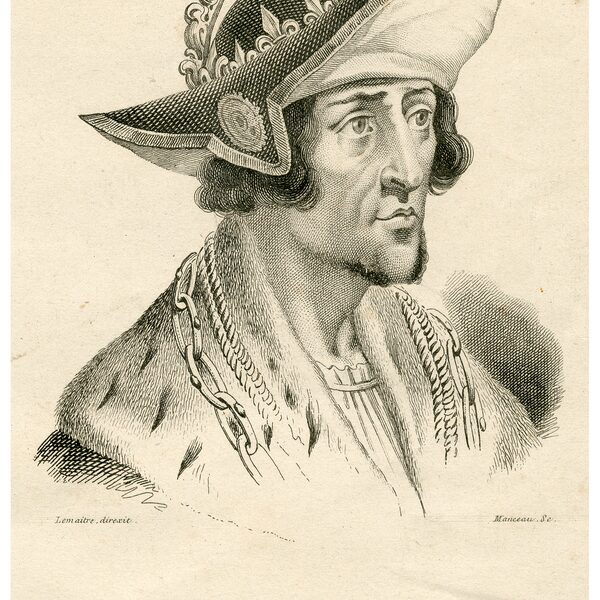

The ties to the House of Nassau determined Wiesbaden's history until modern times. In 1480, Count Adolf III (1480-1511) received Wiesbaden, which thus became the residence of an independent part of the state for the first time. Under the regency of Count Philipp II, the old ruler (1511-1558), the peasants' revolt in the Rheingau spread to Wiesbaden, to which the city ruler responded with draconian punishments. His son Philipp III, the young lord (1558-1566), introduced the Reformation. According to the treaty of December 27, 1554 with his brothers Adolf IV and Balthasar, who belonged to the Teutonic Order, he was to receive Wiesbaden on the death of his father.

As Adolf IV died in 1556 and he himself remained without legal heirs, in 1564, two years before his death, Philipp left Idstein to his brother Balthasar, who resigned from the Teutonic Order in return. After Philipp's death in 1566, he also took over the rule of Wiesbaden. The Wiesbaden-Idstein line died out in 1599 and 1605 respectively. The inheritance fell to the Nassau-Saarbrücken-Weilburg line. Count Ludwig II thus reunited all Welsh possessions in one hand for the first time since the division of 1355.

Ludwig's death in 1627, during a decisive phase of the Thirty Years' War, plunged the Walram counties into a serious crisis. His four sons decided on a new division and each chose an earldom when the treaty was signed in 1629. Count Johannes (1627-1677) opted for the county of Idstein with the lordship of Wiesbaden, Sonnenberg, Wehen and Burgschwalbach. In 1635, their territories were occupied and confiscated and in part sold to imperial retainers. The territory of the County of Nassau-Idstein was divided. The dominion of Idstein was awarded to Prince Schwarzenberg, while the dominion of Wiesbaden was formally handed over to the Elector of Mainz on March 7, 1637. Thanks to an imperial amnesty, Count Johannes von Nassau-Idstein regained possession of the entire county in 1647.

An inheritance dispute arose between Johannes and his last surviving brother Ernst Kasimir and the three sons of his brother Wilhelm Ludwig, which was settled with the Gotha Rezess of March 6, 1651. Count Johannes was awarded the dominions of Idstein and Wiesbaden with the Sonnenberg winery, the Wehener Grund, the Burgschwalbach office, the Idstein portion of the Nassau office and the dominion of Lahr. Ernst Kasimir received the lordship of Weilburg with its appurtenances. The sons of the deceased Count Wilhelm Ludwig divided their possessions in 1659. The Ottweiler, Saarbrücken and Usingen lines were created. The relationship between the houses became increasingly difficult in the following decades, as the respective rulers usually died at a young age and the appointed guardianships pursued their own advantages.

The provisions of the Gotha Recession concerning the compensation payments to be made to each other were also highly controversial. Disputes also arose over estates, imperial fiefs, debt reduction, inheritance issues and elevation to the rank of prince. Prince Georg August Samuel of Nassau-Idstein (1677-1721) and his cousin Walrad of Nassau-Usingen, in particular, campaigned for an elevation in status against the resistance of the Saarbrücken and Weilburg lines. The elevation to the rank of imperial prince in 1688 triggered a dispute over rank among the Walram lines, which was fought out before the Imperial Court Council. Although the Imperial Court granted Georg August Samuel precedence in 1714, his relatives refused to recognize him and refused to pay the associated compensation. The Ottweiler, Saarbrücken, Weilburg and Usingen lines agreed in the Frankfurt Treaty of 1714 that after the death of the sonless Georg August zu Nassau-Idstein, his property would revert to them. When this happened in 1721, Nassau-Ottweiler and Nassau-Saarbrücken took possession of the Idstein estates. Count Friedrich Ludwig zu Nassau-Ottweiler ruled over Nassau-Idstein and thus also over the city of Wiesbaden until 1728. On his death, the inheritance fell to the Nassau-Usingen line, where the dowager princess Charlotte Amalie from the Nassau-Dillenburg line exercised guardianship over her sons Karl and Wilhelm Heinrich.

As the Ottonian lines were also involved in inheritance disputes at this time, a house contract was concluded on 25/30 May 1736, which is regarded as the basis of all later Nassau house contracts. In this treaty, both tribes assured each other of mutual succession in the event of extinction. Charlotte Amalie zu Nassau-Usingen divided the inheritance in 1735, according to which her son Karl (1712-1775) received the possessions on the right bank of the Rhine, including Usingen, Idstein and Wiesbaden, while his younger brother Wilhelm Heinrich (1718-1768) received all the possessions on the left bank of the Rhine. Nassau-Usingen introduced primogeniture in 1754, Nassau-Saarbrücken in 1768. In the hereditary agreement of 1783, these two Nassau branches secured each other's inheritance.

The Saarbrücken line died out with Prince Heinrich in 1799, after France had already occupied the Nassau possessions on the left bank of the Rhine. The Usingen line, which ruled in Wiesbaden, became dukes in 1806, but died out in 1816 with Prince Friedrich August in the male line. It was succeeded in the same year by the Nassau-Weilburg line in the duchy. Duke Wilhelm and his son Adolph zu Nassau controlled the fortunes of the Duchy of Nassau until its annexation by the Kingdom of Prussia in 1866.

Literature

Bleymehl-Eiler, Martina: Stadt und frühneuzeitlicher Fürstenstaat: Wiesbadens Weg von der Amtsstadt zur Hauptstadt des Fürstentums Nassau-Usingen (Mitte des 16. bis Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts), 2 Bde., ungedruckte Dissertation, Mainz 1998.

Even, Pierre: Dynasty Luxemburg-Nassau. From the Counts of Nassau to the Grand Dukes of Luxembourg. A nine-hundred-year history of rulers in one hundred biographies, Luxembourg 2000.