Pheasantry memorial

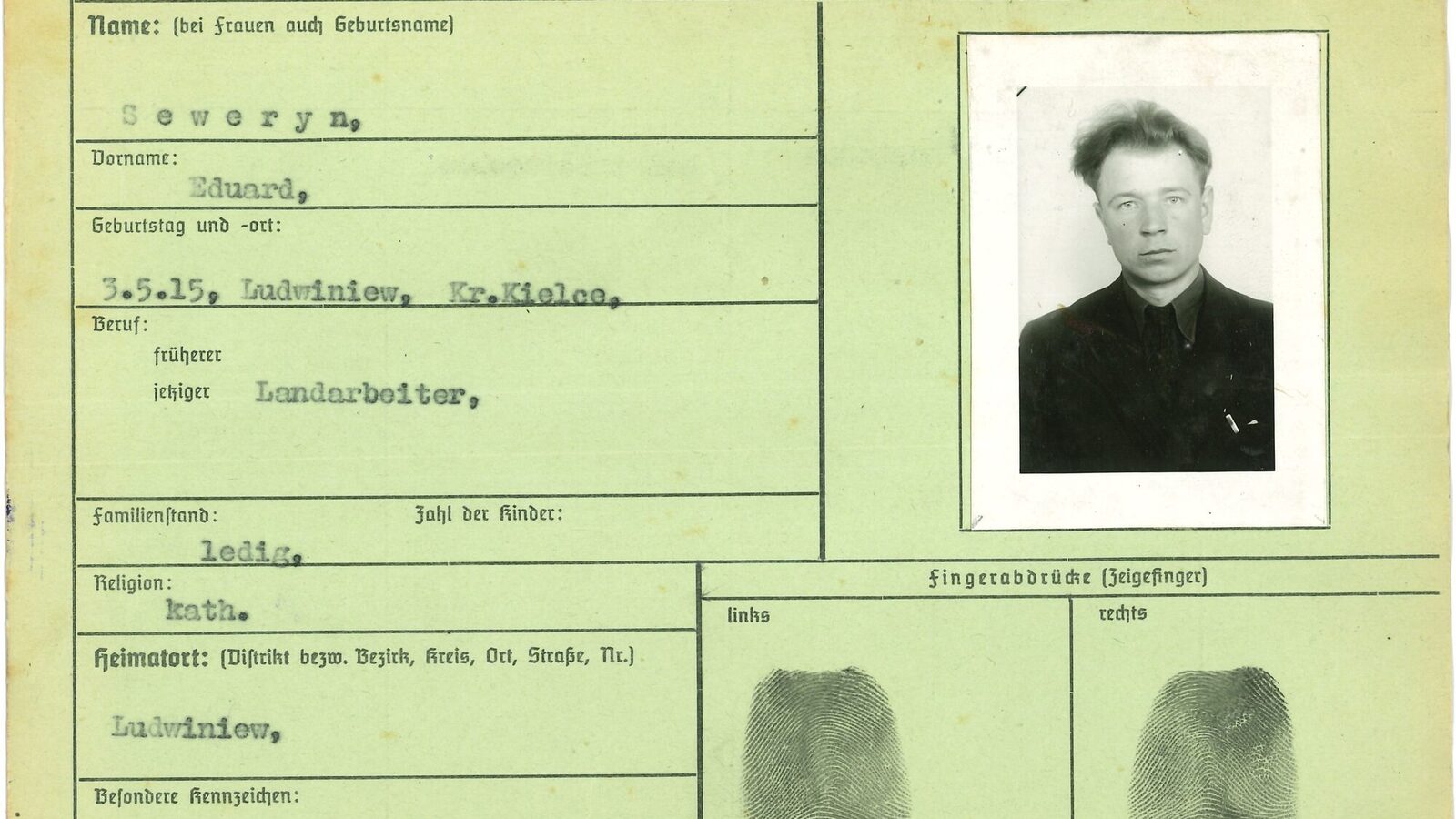

A stele commemorates the Polish forced laborer Edward Seweryn, who was executed at the Fasanerie in 1942.

Forced labor in Wiesbaden - the Seweryn case

During the Second World War, agricultural supplies and the war economy in the German Reich were maintained with the help of forced labor. Between 1939 and 1945, the Wehrmacht and the German labor authorities deported over 13 million people from the territories occupied by Germany to work in the Reich. Forced laborers also worked in Wiesbaden under poor conditions in large companies, medium-sized and small firms and for the city administration. The first forced laborers arrived here in 1940. At the peak of the so-called foreign labor deployment in the summer of 1944, between 6,500 and 7,000 foreign workers had to perform forced labor in Wiesbaden. Among them was Edward Seweryn from Ludwinów in Poland. He had to perform forced labor at the Willy Rauch nursery. He was arrested in 1942. He was accused of sexually abusing his employer's daughter. He was executed in the Fasanerie on July 10, 1942.

Forced labor in the German Reich

Forced labor accompanied the National Socialist regime from the very beginning. Even the prisoners in the early concentration camps were forced to perform hard physical labor. Economic considerations did not initially play a role here. Rather, the aim was to design the conditions of the work in such a way that they were humiliating and had an educational effect in the National Socialist sense. The motive of humiliating those excluded from the "national community" by forcing them to do hard labor continued. This was particularly evident in anti-Jewish measures, such as when Jews were forced to clear the rubble from synagogues after the November pogroms of 1938.

With the invasion of Poland by the German Reich and the beginning of the Second World War, the picture changed fundamentally. Forced labor now became increasingly necessary in order to maintain rearmament and the war economy and to overcome the resulting economic predicaments. Until 1939, there were no extensive preparations for the mass deployment of foreign forced labor. It had only been decided to use Polish prisoners of war in agriculture. However, the situation on the German labor market quickly worsened as a result of the war, which is why the labor authorities decided in November 1939 to recruit Polish workers for agriculture on a massive scale from 1940 onwards.

Polish forced laborers

The deportation of Poles began immediately after the German invasion of Poland. During street raids, the Wehrmacht and police arrested around 20,000 civilians by the end of 1939. Over 420,000 Polish soldiers were taken into custody and around 300,000 of them were deported to work in the Reich. Large-scale propaganda campaigns to recruit volunteers were ineffective, which is why forced recruitment measures eventually prevailed.

While the labor authorities attempted to meet the needs of the war economy through the mass deployment of foreign workers, the German security authorities had considerable reservations about the mass deportation of Poles to the German Reich. They feared "foreign infiltration", espionage and uprisings by foreign workers. As a result, the racist premises of Nazi ideology and the economic requirements of the war came into conflict. As a compromise, particularly restrictive guidelines for dealing with Polish workers were drawn up. The "Polish decrees" came into force on 8 March 1940 and were aimed at racial discrimination and exploitation of Polish forced laborers.

Poles were made subject to compulsory identification. They had to wear the letter "P" on their clothing. There were also numerous restrictions and bans. For example, when the "Polish decrees" came into force, Polish workers were prohibited from using public transport. Of particular importance to the Nazi ideologues was the ban on private contact between Poles and Germans. This applied in particular to intimate relationships, which were often punished with imprisonment in a concentration camp for Polish women and even death for Polish men.

Established procedures for the exploitation of foreign workers from 1939 to 1941, such as the "Polish decrees", served as a model and were further developed in a radicalized form until the end of the war.

The situation of Polish forced laborers was exacerbated by the so-called Polish Criminal Law Decree, which came into force on 4 December 1941. It legally codified the rigorous treatment of Poles by the police and judiciary. From 1942, so-called special courts imposed severe punishments.

Pheasantry memorial

Edward Seweryn, born on March 30, 1915 in Ludwinów, Kielce district, was one of the Polish forced laborers deployed in Wiesbaden from 1940. There is hardly any information about his life. What is documented is that he had to start working for Willy Rauch in the Wiesbaden district of Kleinfeldchen on May 1, 1940. Willy Rauch, who was born on November 10, 1900 in Wiesbaden, had been running a market garden next to the Kleinfeldchen sports field since 1933.

Edward Seweryn was processed for identification by the Wiesbaden criminal investigation department on 21 January 1942. Witnesses stated in the post-war period that Seweryn was accused of sexually abusing his employer's underage daughter. In accordance with the Polish Criminal Code, the case was punished extremely harshly and without due process of law. Officers of the Secret State Police Station in Frankfurt am Main executed Edward Seweryn in the Fasanerie on July 10, 1942. The Fasanerie was a municipal property that was not yet being used as a zoo at the time. It was leased to Dr. Richard Beer, who used it for agricultural purposes. Between 1939 and 1945, at least 26 foreign forced laborers were employed here.

Shortly after Seweryn's death, Katharina Sawtschenko, who came from Kiev, was put to work in the Willy Rauch nursery. She was followed on May 2, 1944 by Stanislaw Wroniewicz, who was just 17 years old.

The long-term war against the Soviet Union and the increasing demand for labour in the armaments industry in particular led to the centralization of labour policy from 1942 onwards. On March 21, 1942, Fritz Sauckel (1894-1946) was appointed "General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment". After the defeat at Stalingrad, labour policy was further radicalized and the "deployment of foreigners" was expanded enormously in all areas. Prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates were increasingly used for labor, resulting in the development of an extensive network of POW and concentration camp satellite camps. For the civilian workers from the Soviet Union who were deported to the German Reich from spring 1942, a comprehensive special law was created along the lines of the "Polish decrees".

The system of "deployment of foreigners" thus created remained in place until the final weeks of the war. The bombing of German cities and the turmoil of the last days of the war threatened the lives of the forced laborers. On March 9, 1945, the largest forced labour camp in Wiesbaden was destroyed. As the foreign forced laborers were forbidden to go to shelters, over 20 people died as a result of the bombing of the camp, which was located near the Wiesbaden slaughterhouse. With the destruction of the camp, all structures for supplying the forced laborers also collapsed. The foreign workers wandered through the city looking for ways to procure food. They were liberated when the US army marched in on March 28, 1945. Most of the survivors remained in Wiesbaden for several months as "displaced persons" until the military government was able to transfer them to their home countries.

In the course of the legal investigation into Nazi crimes in the 1950s and 1960s, Seweryn's death was also investigated by the Hessian State Criminal Police Office in Wiesbaden. The unknown perpetrators were investigated for murder.

Between 1962 and 1964, the detectives questioned former officers of the Secret State Police in Frankfurt am Main and its branch office in Wiesbaden, among others. The investigations revealed that Bernhard Weyland, an assistant officer with the Frankfurt Gestapo, carried out the execution. Other officers, including the head of the Frankfurt Gestapo Oswald Poche, are said to have taken part in the execution. In his interrogation, Weyland also stated that around ten Polish forced laborers were forced to attend Seweryn's execution. This served as a deterrent and was intended to spread fear among the forced laborers.

The proceedings against the officials responsible for carrying out the execution were dropped by the senior public prosecutor at Frankfurt am Main Regional Court on January 6, 1968. Either the accused could not prove their involvement in the execution beyond doubt or, as in the case of Weyland, they claimed to have carried out orders from their superiors without realizing that they were participating in a crime.

An information stele at the entrance to Tierpark Fasanerie has commemorated forced laborers deported to Wiesbaden since 2025. The case of Edward Seweryn and his execution are also critically examined on site.

City archive

Address

65197 Wiesbaden

Postal address

65029 Wiesbaden

Arrival

Notes on public transport

Public transportation: Bus stop Kleinfeldchen/Stadtarchiv, bus lines 4, 17, 23, 24 and 27 and bus stop Künstlerviertel/Stadtarchiv, bus line 18.

Telephone

- +49 611 313022

- +49 611 313977

Opening hours

Opening hours of the reading room:

- Monday: 9 a.m. to 12 p.m.

- Tuesday: 9 am to 4 pm

- Wednesday: 9 am to 6 pm

- Thursday: 12 to 16 o'clock

- Friday: closed