Franconia

Wiesbaden and the surrounding area have been influenced by the Franks since the beginning of the 6th century. Although there are no written sources from this period, various finds of terraced graves bear witness to the life of the Franks in the Wiesbaden region.

Just as the Alemanni formed in the 3rd century A.D. as a community of interests with the aim of sharing in the riches of the Roman province of Germania Prima, Germanic tribal groups based in the right bank of the Rhine in the province of Germania Secunda came together at around the same time to form the ethnic association of the Franks. Their name was their program: it means something like "the bold", "the daring" - our word "bold" is etymologically and in meaning related to it.

What the Franks accomplished in the 3rd, 4th and 5th centuries in pursuit of their primary political goal, by invading the Roman territories to the left of the Rhine, and also by settling there, initially tolerated by the Romans, and finally by their own authority, did not directly affect Wiesbaden and its surrounding area. This changed when, after the end of the Roman Empire, the Alemanni pushed northwards beyond their own territory, particularly on the left bank of the Rhine, and thus came into conflict with the Franks.

The Battle of Zülpich fought between the Franks and Alemanni in 496/97 AD marks the furthest advance of the Alemanni in terms of time and space. In turn, the Franks subsequently pushed the Alemanni back to the south and extended their own territory far into the Upper Rhine Plain. As a result, the region at the mouth of the Main, which had previously been ruled by the Alemanni, and thus also Wiesbaden, came under the rule of the Franks, just like Mainz: Wiesbaden and its surrounding area had been Frankish since the beginning of the 6th century.

There is no evidence that this was associated with a radical change in population. Distant descendants of the long-established provincials, Germanic tribes of Alemannic descent, one or two immigrant groups of Franks and undoubtedly many Thuringians and East Germanic tribes who had moved to the Rhine from the interior of Germania probably formed the basis for a population that was diverse in terms of origin but quite uniform in terms of cultural habitus.

For the epoch of the early Middle Ages following the end of antiquity, which is often referred to in our region as the "Frankish period" after the relevant people or as the "Merovingian period" after the ruling dynasty, the written sources are silent with regard to Wiesbaden. Only the archaeological finds fill this vacuum, and it is mainly grave finds that provide this evidence.

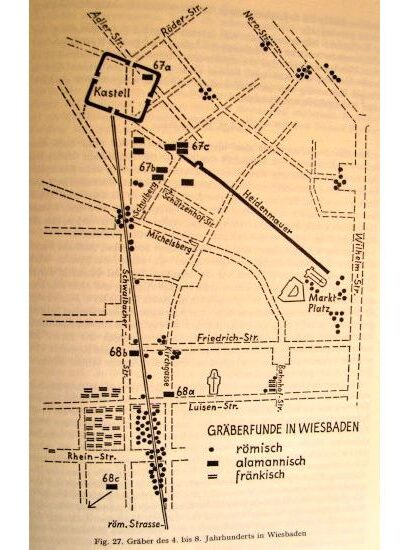

A large terraced burial ground from the Franconian period has been discovered in the inner city area of Wiesbaden on Schwalbacher Straße in the section crossed by Rheinstraße and Luisenstraße/Dotzheimer Straße. Here, on the old Schiersteiner Weg, burials containing grave goods from the early Middle Ages have repeatedly come to light, especially in the 19th century: male graves with weapons and female graves with jewelry. Ultimately, this cemetery is in the tradition of the cemetery that was already established in the same area in Roman times on both sides of a road leading southwards from the stone fort, where individual dead also found their final resting place in the Alemannic era. The extensive finds indicate that this cemetery was occupied as early as the 5th century, strictly speaking in the Alemannic period.

The older Merovingian period (6th century) is documented by a particularly large number of finds, but the more recent period of the 7th century is also clearly attested by characteristic forms. There is evidence of elaborate grave furnishings in the form of numerous glass and bronze vessels, among other things, indicating the burial of people who belonged to a higher social class. The considerable number of long swords and special lances (angones) also point in this direction.

It should be emphasized that half a dozen early Christian gravestones have also come to light in the area of this cemetery, a very uniform group in terms of format and design, all bearing the Christogram as a distinctive symbol and with short inscriptions. They not only testify to what could not be doubted anyway, namely that Christianity had found its way into Wiesbaden in the 5th/6th century, but they also provide us with some of the names of Wiesbadeners living at the time: Eppo and Ingildo, Municerna and Qalaqit, Runa and Votrilo.

There can be no doubt that the homes of the people buried along the old Schiersteiner Weg in the course of the Frankish period were located in the area of the springs, which had been settled since Roman times; however, there is a lack of archaeological evidence for this, apart from a few isolated finds. It was only in the following period that this core area of the city of Wiesbaden emerged more clearly in the light of written and material sources.

If one considers the surroundings of this core area, as far as it belongs to the urban area of Wiesbaden today, it is first necessary to refer to a second place that was created in Roman times and has remained continuously populated beyond Roman times to the present day: Kastel (Castellum Mattiacorum), the bridgehead of Mogontiacum/Mainz on the right bank of the Rhine. Not only was the settlement area itself used continuously, but also the cemetery outside the walls, which has been documented since Roman times. It extended along the arterial road leading down the Rhine or to Aquae Mattiacae/Wiesbaden; considerable finds from the Frankish period are also known from there.

In addition, numerous Merovingian grave finds from the suburbs that today belong to the city of Wiesbaden document the settlement in the rural surroundings of the core settlement that emerged from the Roman vicus Aquae Mattiacae in the early Middle Ages. Grave complexes have been discovered in or near Bierstadt, Erbenheim, Igstadt, Kloppenheim, Kostheim, Nordenstadt and Schierstein, which can be referred to as the Merovingian local cemeteries of these places. The date of the grave finds also provides a reliable indication of the existence of the site in question. For example, the original prehistoric settlement of Schierstein already existed around the middle of the 5th century, according to particularly early grave finds.

Similarly, Bierstadt, Erbenheim, Igstadt, Kostheim and Nordenstadt are already known to have existed in the 6th century - in other words, long before the appearance of written, documentary evidence. Even a single farmstead such as the Grorother Hof in the old Frauenstein district can claim early medieval origins with reference to associated grave finds from the 7th century.

Sometimes isolated burial complexes can point to abandoned settlements (deserted sites), such as the exceptionally early finds in the Biebrich area (Waldstraße and Siegfriedstraße), which can be assigned to the 5th century, and others within the Kostheim area east of the Käsbach stream.

Literature

- Geuenich, Dieter

The Franks and the Alamanni up to the "Battle of Zülpich" (496/97). Supplementary volume to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 19, Berlin/New York 1998.

- Boppert, Walburg

Die frühchristlichen Inschriften des Mittelrheingebietes, Mainz 1971 (pp. 141-152).

- Buchinger, Barbara

The early medieval grave finds from Wiesbaden. Europäische Hochschulschriften, Series III, Volume 751, Frankfurt a. M. 1997.

- Böhme, Horst Wolfgang

Hesse from Late Antiquity to the Merovingian period. In: Berichte der Kommission für Archäologische Landesforschung in Hessen 12, 2012/13 (pp. 79-134).