Institute for Artificial Eyes F. Ad. Müller Sons

At the instigation of Wiesbaden ophthalmologist Dr. Alexander Pagenstecher, Friedrich Adolph Müller moved his workshop for glass eyes from Lauscha to Wiesbaden in 1875. To this day, the company is known worldwide for the production of artificial eyes.

The production of artificial eyes for humans can be traced back to the 16th century. As early as 1560, the French surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510-1590) described two types: the "pre-laying eye" (ecblepharon), a plate covering the eye socket with a painted eye, and the "inlay eye" (hipoblepharon), which was inserted into the empty eye socket behind the eyelid. For the latter, enameled or enamel-coated silver or copper shells were initially used, but these were very heavy and irritated the orbital tissue due to their sharp edges. They were also only used for a short time because the lacrimal fluid corroded the enamel coating. For this reason, bowls made of glass were developed in Venice and France, which were more malleable and lighter and could be used to reproduce the human eye "beautifully and deceptively realistically".

From the middle of the 18th century, glass eye artists in Paris took over the leading role in this field. They used lead glass to make the bowls.

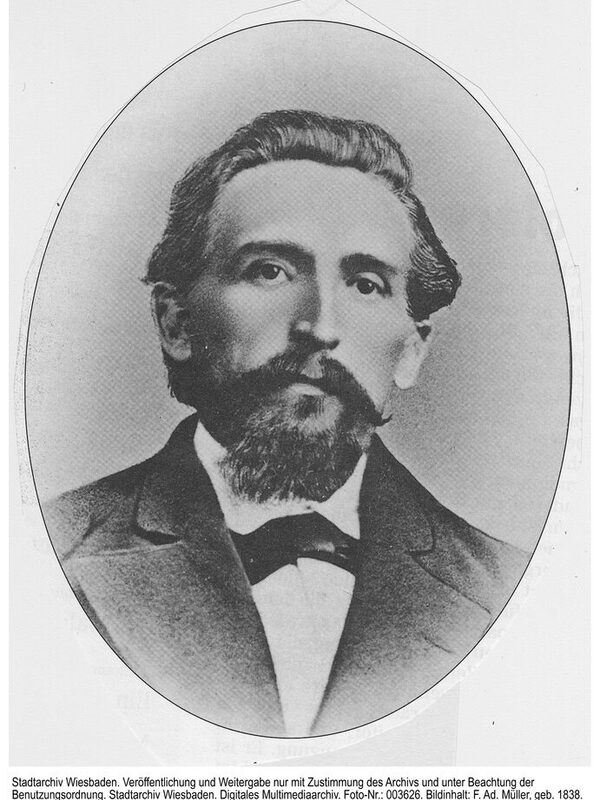

Friedrich Adolph Müller (1838-1879), son of the master butcher and Lauscha mayor Friedrich Müller (1809-1879) and Johanna Elisabeth Friedrike Müller, née Schönheit (1798-1862), had learned to make animal, doll and human eyes from his uncle Ludwig Müller-Uri. Schönheit (1798-1862), had learned the production of animal, doll and human eyes from his uncle Ludwig Müller-Uri, founded his own workshop for glass eyes in Lauscha in 1860 and since then, together with the master glassmakers Christian Müller-Pathle, Septimius Greiner-Kleiner and August Greiner-Wirth, tried to develop a tear-resistant material.

The breakthrough came in 1868 with the addition of the natural raw material ice stone or cryolite from Greenland, which increased the wearability of the artificial eyes to over twelve months. Thanks to its hard, smooth and tear-resistant surface, cryolite glass became established for the manufacture of ocular prostheses in Europe and eventually around the world and is still used today.

In 1875, Friedrich Adolph Müller, his wife Amanda Müller née Greiner (1839-1906) and their seven children moved their residence and workshop to Bleichstraße 9 in Wiesbaden at the instigation of the ophthalmologist Hofrat Dr. Alexander Pagenstecher (1856-1879), director of the ophthalmological clinic in Wiesbaden.

A short time later, the "manufacturer of artificial eyes" acquired a building in Rheinstraße, where his wife Amanda continued to run the company after his death in 1879. On January 1, 1887, his sons Friedrich Müller (1862-1939) and Albert Karl Müller (1864-1923) founded the company "F. Ad. Müller Söhne, F. u. A. Müller, Wiesbaden", which acquired the building in today's Taunusstrasse 42 in 1891 and the building in today's Taunusstrasse 44 in 1893; the latter still serves as the company headquarters today.

From 1904, the company traded under the reduced name "F. Ad. Müller Söhne" but with the additions "Atelier" and "Institut für künstliche Augen". The proximity to the Wiesbaden Eye Hospital and the demand for ocular prostheses at home and abroad quickly filled the order books and made the company world-famous. As early as 1907, the Atelier für künstliche Augen was treating around 6,000 patients a year; today it treats around 10,000 patients a year, half of them from Germany and the other half from neighboring countries such as Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Austria.

The family, which has officially borne the surname "Müller-Uri" since 1937 with the approval of the Wiesbaden district court in reference to the family branch from Lauscha, is now the fifth generation to run the company in Wiesbaden.

Literature

A walk through the Thuringian toy country, In: Die Gartenlaube, 1883, issue 17 (pp. 279-282).

Industry, trade and commerce. The administrative district of Wiesbaden, Berlin 1913 (2nd edition).