Dyckerhoff & Widmann (Dywidag)

The company Dyckerhoff & Widmann was founded in 1865 by Wilhelm Gustav Dyckerhoff as a factory for precast concrete parts. In addition to pipes, it initially also produced building ornaments and fountains, such as the "Galatea Fountain" in Biebrich. It later became well known for its innovative designs and prestigious buildings; the Wiesbaden site was closed in 2004.

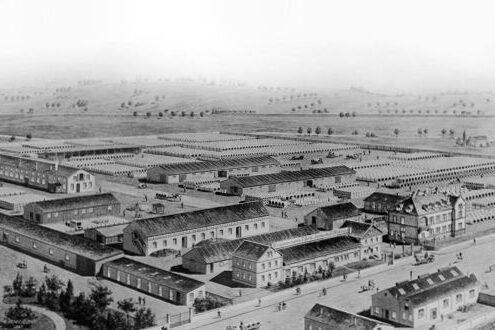

In 1865, Wilhelm Gustav Dyckerhoff, a partner in the Amöneburg cement works Dyckerhoff & Söhne(Dyckerhoff GmbH), founded a small factory for precast concrete parts in Karlsruhe with two partners. One year later, his son Eugen Dyckerhoff took over the technical management of the company and named it "Dyckerhoff & Widmann" after his father-in-law Gottlieb Widmann joined in 1869. Eugen Dyckerhoff left the management of the Karlsruhe company to Gottlieb Widmann. He himself moved to Biebrich and opened a first branch east of the former Rhine barracks. In the following years, Eugen Dyckerhoff carried out extensive tests to improve the concrete formulas with the laboratory of the Amöneburg cement works. The Dyckerhoff & Widmann company initially used the new building material to produce concrete pipes and artistic products such as architectural ornaments, figures and fountains. A vase on a pedestal from the early range and the so-called "Galatea Fountain", which Eugen Dyckerhoff donated to the city in 1900, still exist today in the Robert Krekel complex in Biebrich.

Supported by master builder Alexander Fach and city planning director Ernst Winter, Dyckerhoff & Widmann received its first civil engineering contracts in Wiesbaden. In 1869, they constructed a water pipeline made of concrete pipes for the city and in 1882, the first major concrete construction was a water tank on Platter Straße with a volume of 4300 m3. Pipelines and underground tanks were followed by the construction of concrete bridges throughout Germany from the end of the 19th century. In Wiesbaden, Dyckerhoff & Widmann built several railroad bridges at the beginning of the 20th century as part of the expansion of today's Wiesbaden Ost railroad station. At the same time, the company worked on more and more orders for prestigious buildings. One of the most sensational buildings of this period, the Jahrhunderthalle in Breslau (1911/12), is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site due to its innovative design. The firm's best-known projects in Wiesbaden include the work on the Henkell sparkling wine cellar (1907/08) (Henkell & Co., Sektkellerei) and the Municipal Museum (1914/15) (Museum Wiesbaden).

In 1907, Dywidag moved its headquarters to Biebrich. From here, it managed its dense network of branches in Germany and the increasing number of major projects abroad. From the mid-1920s, the company carried out preliminary work in Biebrich for the globally successful Zeiss-Dywidag construction system, which made it possible to build domes and vaulted roofs with concrete shells just a few centimetres thick. A test dome from 1931 has been preserved and is now located on the Dyckerhoff GmbH premises in Amöneburg. During the Second World War, Dyckerhoff & Widmann used Zeiss-Dywidag shells to roof the production halls of the Volkswagen factory, among other things. In the post-war period, the company made its mark internationally with further innovative processes such as prestressed concrete construction and cantilever construction. Since the company headquarters were relocated to Berlin in 1935 and from there to Munich in 1945, the Wiesbaden-based company lost importance. From the end of the 1970s, the concrete plant of the branch now located in Erbenheim was gradually shut down. In 2001, Walter Bau-AG took over the company Dyckerhoff & Widmann. The insolvency of Walter Bau just four years later led to the break-up of the former Dywidag and the closure of the traditional Wiesbaden site.

Literature

- Dyckerhoff & Widmann AG (Hrsg.)

Dywidag illustrated book. Buildings of Dyckerhoff & Widmann AG 1865-1990, Munich 1990.

- Stegmann, Knut

The construction company Dyckerhoff & Widmann. On the beginnings of concrete construction in Germany 1865-1918, Tübingen/Berlin 2014.