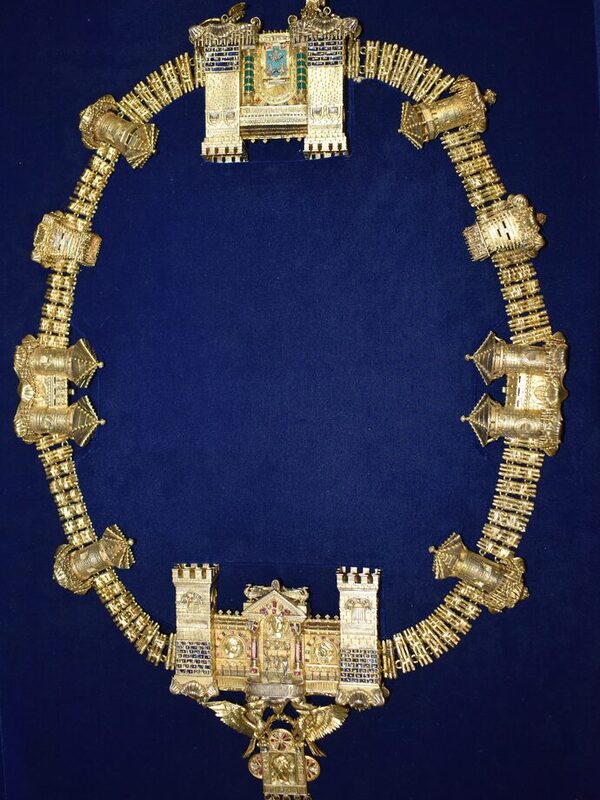

Chain of office of the Lord Mayor

An imperial "gift of grace": the chain of office from 1897

The oldest chain of office in Wiesbaden is a gift from Emperor Wilhelm II. In May 1897, the Prussian Court Marshal's Office commissioned the director of the Strasbourg School of Applied Arts, Prof. Anton Seder, to make a golden chain of office for Wiesbaden worth around 5,000 marks. Seder's design was realized by the Munich court goldsmith Theodor Heiden.

The magnificent piece of jewelry, weighing around 1,500 g, depicts the stylized, historically inspired Limes with a palisade fence and watchtowers as links. The chest piece is particularly lavishly decorated with gemstones and is designed as a gabled fountain, a reference to Wiesbaden's importance as a thermal spa in Roman times. The lower end is formed by a pendant flanked by two eagles with the profile portrait of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the inscriptions "WILHELM IMPERATOR" and "REX.GERMAN" ["Wilhelm German Emperor and King"]. The back of the chain is in the shape of a city gate with two watchtowers, archway and battlements as well as the city's coat of arms. It bears the inscription "SENAT[US] POP[ULUS]QU[E] MATTIA" ["The Senate and the People of Wiesbaden"]. On the reverse, reference is made to the two artists: "fecit/Th. Heiden/Munich" and "invenit/A. Seder/Straßburg".

On October 18, 1897, the "gift of grace" was presented to Lord Mayor Karl Bernhard von Ibell in the palace by the Emperor himself. Until his abdication, Kaiser Wilhelm reserved the right to authorize the respective mayor to wear the chain, a right that was initially denied to Lord Mayor Karl Glässing in 1913, for example. In 1917, he informed all those entitled to wear gold official insignia that they were allowed to wear chains made of iron or other war metals with the same inscriptions until further notice if they wished to donate them to the Reichsbank's gold collection. When the people of Wiesbaden then wanted to have the chain of office melted down, it turned out that it was not made of gold, as previously assumed, but of gold-plated silver. It is thanks to this fact that the chain of office has survived to this day.

A long road to a new chain of office

As early as the end of the 1930s, the city's main office proposed replacing the existing chain of office of the Lord Mayor of Wiesbaden with a new chain, because the chain donated by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1897 no longer corresponded to modern views in terms of form and content and it was only possible to wear the chain with the aid of special carrying devices. For this reason, the old chain of office had not been officially used in Wiesbaden since 1918. In addition, the National Socialist Ministry of the Interior took offense at the fact that chains of office with the Kaiser's likeness, i.e. with the insignia of the "old Reich", were still in use and prohibited their use.

The outbreak of war prevented the proposal from being implemented. At the end of 1949, the main office took up the matter again and submitted a corresponding proposal to the magistrate, which was approved in principle. It was suggested by the honorary members of the magistrate that the cost of producing the chain of office should not be borne by the city, but that the funds should be raised by donations from the citizenry if possible. This idea was put into practice through a collection initiated by the honorary councillors Bachmann, Gitter, Glücklich and Schneider. The appeal signed by these gentlemen was primarily aimed at the industrial, commercial and trade circles. The amount to be raised was donated almost in full; it was not least a recognition of the reconstruction work carried out.

The design and execution of the chain of office took a long time, because it was only after various ideas and drafts that the final proposal was finally made to design the chain from original coins documenting the historical development of Wiesbaden. This proposal was made after consultation between the director of the Werkkunstschule Weber and the well-known master goldsmith Elisabeth Treskow from Cologne and was approved by the city council at its meeting on November 11, 1955, with a simultaneous order to take the coins required for the necklace from the museum's holdings. As not all of the required coins were available in the city museum's coin collection, it was necessary to purchase some missing pieces, which also took some time.

The chain of office was then designed in 1956 by the director of the Werkkunstschule, Vincent Weber, at the request of the magistrate. The craftsmanship was carried out by the Wiesbaden master goldsmith Carl Struck, who donated the lapis lazuli (glaze stone) and a coin in addition to his unselfish work.

With the exception of two silver coins, the necklace shows only gold coins. The row of coins is interrupted by two faithful replicas of Frankish fibulae (garment pins) with almadin inlays (garnet stone). The individual coins are each set in a round groove, which is set off at the edges by highly polished square wires. The individual coins are set on hallmarked gold plates in such a way that the reverse of the coins remains visible. The individual coin links of the chain are each connected by eyelets to a smaller chain link, which consists of a square rolled gold wire with a Wiesbaden lily in the middle. The pendant of the necklace is the coat of arms of the city of Wiesbaden in the same technical design as the coin links and shows the three golden lilies of the city on the genuine lapis lazuli in the center. The entire chain is made of 585/000 gold.

The lowest coin depicts the Roman general Drusus Germanicus (38 to nine BC), under whom the Roman offensive wars against Germania up to the Elbe were waged in the Augustan period. It was during this period (probably twelve BC) that the first earth fort was erected on the Heidenberg. - To the right of the observer, the second coin image is that of Emperor Tiberius (14 to 37 AD), under whom renewed fighting against Germania took place. The second coin shows the image of Emperor Domitian (81 to 96 AD), during whose reign the Roman stone fort on the Heidenberg was built. The third coin shows the image of Emperor Hadrian (117 to 138), under whom the garrison of the Wiesbaden fort was relocated to the Saalburg in the course of the reorganization of border defence in 121/22 and Wiesbaden (Aquae Mattiacorum) became an open civic city. On the opposite side, the third coin shows Emperor Valentinian I (364 to 375).

The fourth link, a Frankish disk brooch, indicates the time of the Franks. The fifth large link in the chain is a coin from the time of Charlemagne (768 to 814). Charlemagne's biographer Einhard, who stayed in the "castrum Wisibada" in 829, was the first to record the German name of Wiesbaden.

The fifth coin shows a stylized imperial eagle on a coin from the time of Emperor Frederick II, the great Hohenstaufen emperor, who celebrated Pentecost in Wiesbaden with his third wife, Isabella of England, in 1236 and during whose reign Wiesbaden was named as an imperial city. The sixth coin on the left side of the chain - in silver - dates from the reign of Count Johann Ludwig I of Nassau (1568-1596), who issued a charter of freedom to the city of Wiesbaden in 1592 and built the New Palace in the city. The sixth silver coin on the right is a denarius of Emperor Otto I (936-973), who visited Wiesbaden in 965, probably because of the Mauritius Church.

The following, seventh coin on the left goes back to Count Walram II of Nassau (1370-1393), who issued the first known letter of freedom for Wiesbaden. The seventh coin dates from the time of Count Gerlach of Nassau (1285-1361). After resigning from the government in 1344, he lived at Sonnenberg Castle until his death in 1361. The eighth coin link is a coin of Ruppert von Sonnenberg (1355-1390), followed on the other side by the image of the Nassau Duke Wilhelm (1816-1839), who united the entire Nassau lands in his hands and whose memory is kept alive by the Wilhelmstraße named after him. The final link in the chain is a gold piece with the image of Kaiser Wilhelm I (1797-1888) as a representative of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

Literature

Koch, Michael; Weidisch, Peter (ed.): Theodor Heiden, Königlich bayerischer Hofgoldschmied, Würzburg 1997, pp. 63/64.

Neese, Bernd-Michael: The Emperor is coming! Wilhelm I and Wilhelm II in Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2000, p. 48 f.