Carl Theodor Wagner, electrotechnical factory

The Carl Theodor Wagner clock factory was a traditional Wiesbaden-based company. With its patent for an electro-pulse-controlled system of master and slave clocks, it supplied clocks mainly for churches, town halls, railroad stations, schools, hotels, factories and hospitals in large cities all over the world.

Carl Theodor Wagner (20.05.1826-28.03.1907) opened a one-man workshop in 1852 after an apprenticeship as a clockmaker and years of traveling and working as a journeyman in his hometown of Usingen. Together with the Kassel entrepreneur Heinrich Grau, he developed the Grau-Wagner patent, the basis for the production of large clocks in Wiesbaden. It began in 1863 in a workshop with a four-horsepower gas engine in Wiesbaden's Goldgasse, initially No. 2, later No. 6. For a time, master watchmaker Wagner trained with Prof. Heinrich Meidinger in Heidelberg, who initiated him into the secrets of electromagnetism.

In the meantime, Duke Adolph zu Nassau had become aware of Wagner's technical talent. He supported Wagner by sending him to the world exhibitions in London (1862) and Paris (1867). In 1879, Wagner received a patent from King Wilhelm of Prussia for an "electrical apparatus for producing slow strokes on electric bells". The automatically striking church clock was thus invented.

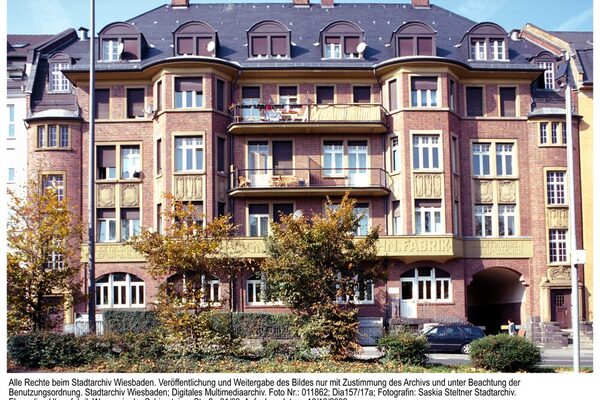

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, Wagner's watch business boomed. From 1880 onwards, Wagner was the main supplier of clocks for the Reichsbahn. In 1885, the company moved to Mühlgasse, and in 1915 to Schiersteiner Straße 31-33, where a new production, commercial and residential building had been built. It offered space for 600 employees, but the First World War prevented further expansion. Wagner's four sons also worked in the company.

Over 100,000 clocks were delivered in the first 100 years until 1952. Wiesbaden's town hall was also equipped with a Wagner system, from whose control center in the basement all public clocks in the city were controlled. Even the clocks of the bakers and other small businesses were connected to the town hall central clock. More than 50 secondary clocks are said to have been connected to the central clock at Frankfurt Central Station. In Bombay, there were allegedly as many as 350 slave clocks controlled from a hotel, some with dials over two meters in diameter.

The importance of Wagner clocks can be measured by the fact that only the wealthy could afford a pocket watch or wristwatch at the time. There were also many Wagner clocks in Wiesbaden schools. Today, there may still be Grau-Wagner clocks at the Oranienschule, the chapel of the Paulinenstift and in the Kunsthaus, the former elementary school on Schulberg.

When quartz clocks appeared in the 1960s, clocks based on the Grau-Wagner principle were soon no longer worthwhile. In 1989, when the Wiesbaden town hall was renovated, the Wagner system was scrapped. Finally, fully electronic quartz clocks were produced in Schiersteiner Strasse, including for Siemens and Standard Elektronik Lorenz, as well as display panels for sports facilities. In November 1977, the traditional Wiesbaden factory with 77 employees had to file for bankruptcy. The company was no longer able to cope with the worldwide competitive pressure from other quartz clock manufacturers.

Today, Wagner clocks can still be found in Rome, Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and in the former German East Africa, in Sydney and St. Petersburg.

Literature

Spiegel, Margit: Wiesbadener Firmenbriefköpfe aus der Kaiserzeit 1871-1914. Fabrik- und Hotelansichten auf Geschäftsschreiben und Rechnungen. 50 examples with brief company portraits, vol. 1, Wiesbaden 2003 [p. 144 ff.].