Wiesbaden originals

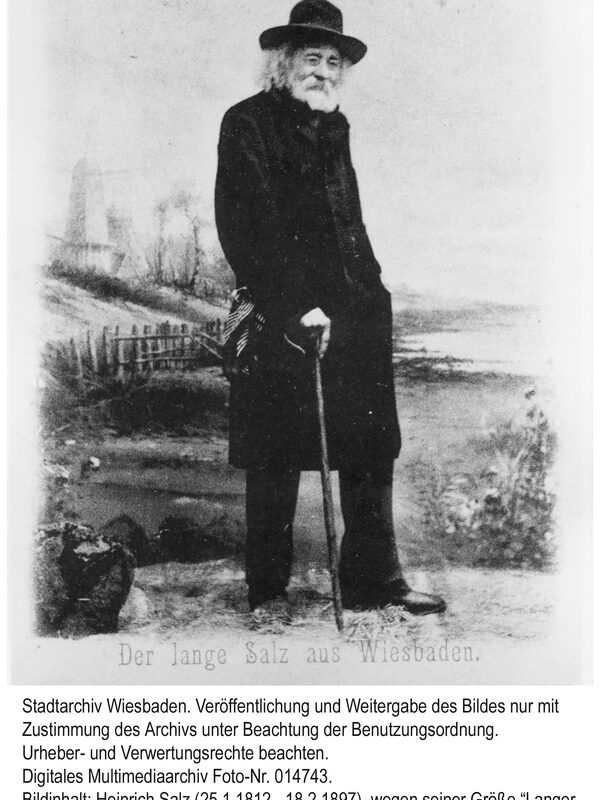

The most popular Wiesbaden original was Heinrich Saltz, born on 25.01.1825 at the Kupfermühle in Mühltal, known as the "long Saltz" because of his height. He earned his living by performing songs and ballads and selling postcards in Wiesbaden's pubs. Born on January 29, 1830 in Freiendiez, Karl Peter Philippar fell out with his church superiors after studying theology and initially settled in Wiesbaden as a private teacher. However, due to his eccentric nature and quirky behavior, his students dried up over the years. Philippar, who was known as "the eternal student" due to his academic appearance and unkempt appearance, was eventually no longer able to support himself and had to rely on poor relief. He died on 29.11.1896 in Wiesbaden.

Philipp Keim was born on November 7, 1804 in Diedenbergen. After training as a cooper, he worked as an assistant in the ducal winery in Biebrich, where he was blinded in a tragic accident. As compensation, Duke Wilhelm zu Nassau had a barrel organ bought for Keim and allowed him to play music throughout the duchy. From then on, Keim toured the spa towns and resorts and became known to a wider audience with moritats about the explosion of the Mainz Powder Tower in 1847, the Kauber landslide of 1874 and the assassination attempts on Kaiser Wilhelm I, among other things. His wife Lisbeth accompanied him on the violin during his performances. Their fame helped the two musicians to achieve a certain level of prosperity, such as owning their own horse-drawn carriage. Philipp Keim died shortly before his 80th birthday in July 1884.

The bookseller and dialect poet Franz Bossong, known as "Lord Blummekohl", became an original thanks to his appearances as a carnival speaker at the "Sprudel" carnival club around 1900. Bossong, like the dentist Paul Rehm and the security guard Max Schwencke, was a regular at a pub run by Friedrich Grupp on the upper Hochstätte at the turn of the century. The innkeeper was nicknamed "Juckmich" or "Schlaumeier vom Säumarkt" due to his nervous shoulder shrug and above-average intelligence. He regularly discussed issues of world history with his guests. Grupp's story in Wiesbaden ended at the same time as the outbreak of the First World War and the death of his friend Bossong.

One of the few female originals was Helene Best, who was known as "Stricklenchen" in Wiesbaden in the last years of the imperial era and at the beginning of the 1920s. Always simply and neatly dressed, she could usually be found in the archway in the west wing of the town hall. Her nickname had a double meaning. On the one hand, she was never seen without her knitting, which she always carried with her in a wicker basket. On the other hand, she would recite lyrical verses on all occasions, such as christenings or weddings, and thus, in a figurative sense, also "self-knitted". Thanks to her good relations with the registry office, she was always informed about upcoming festivities and soon became an indispensable part of every major family celebration.

Waldemar Reichhard studied singing at the Mainz College of Music in the 1930s. He was nicknamed "Garlic" because of his fondness for leeks. Today, a memorial in Kleine Schwalbacher Straße commemorates him.

Willi Benz, known as "Williche", made a name for himself as a sweeper around the St. Elisabeth community center in the second half of the 20th century. The mentally disabled man lived with his parents in Westend and made it his job to keep the paths around the community center clean. He continued this work even after moving to the Biebrich retirement home following the death of his parents. He was one of the most popular originals in recent history. Willi Benz died at the age of 79 in January 1988.

In addition to these Wiesbaden originals who frequently appear in the city's history, there are also occasional names of people such as the "Fire King", a homeless man whose night camp in Wellritztal once started a wildfire. Equally popular in their day were "Lumpen-Rosa" and "Lumpen-Fritz", who gained questionable fame in the years before the First World War due to their run-down appearance, their crude rants and their penchant for petty theft. Rosa's son, the so-called Brezelbub, on the other hand, was well-liked by the people of Wiesbaden, as he always carried the pretzels and other baked goods, covered with a blue and yellow linen cloth, to the suburbs on foot in a blue and white striped smock. The nickname "Bub" was given to him by the "Stricklenchen" because of his small size.

Literature

Fink, Otto E.: Wiesbadener Bildchronik 1866-1945, Wiesbaden: no year.

Leidenbach, Wilhelm: Wiesbaden originals in modern times. In: Wiesbadener Leben 4/82 [p. 22].

Trautner, Hanns: Wiesbadener Originale. Series. In: Wiesbadener Leben 8/1970 to 1/1971.