City fortifications

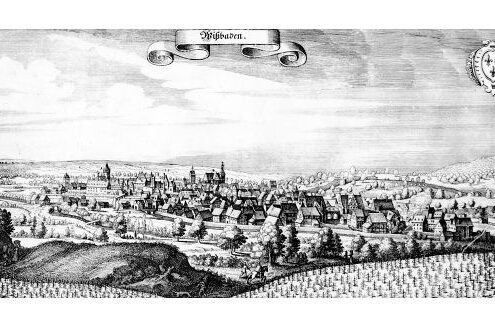

The construction of Wiesbaden's town fortifications began in the 13th century. However, for around 200 years, until 1508, only the castle district was fortified as one of the three settlement cores. Only then was the "suburb" included in the fortifications. For the "Sauerland" and its rural population, a fortification of ponds and ramparts was sufficient until the 18th century.

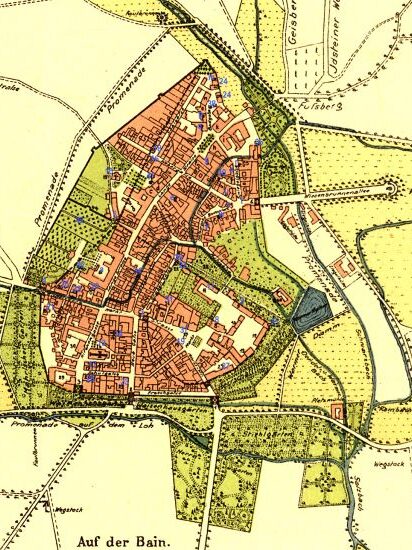

In the course of the disputes between the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II and the German sovereigns and the Pope, Wiesbaden was probably elevated to the status of an imperial city in the early 1230s. However, the city did not have adequate fortifications. This is shown by the fact that Wiesbaden was exempted from taxes in 1241 in order to use these funds "ad edificia". It is assumed that this entry in the imperial tax list is a paraphrase for the construction or renovation of the city wall. After the destruction of Wiesbaden in the following year, its expansion was not continued until the end of the 13th century and was completed under Count Gerlach I of Nassau-Idstein (ca. 1283-1361) in 1305. Until 1508, however, only one of Wiesbaden's three settlement centers was fortified, namely the castle district, the "Feste Wiesbaden, Burg und Stadt" mentioned in 1352. On its northern side, the fortification used the Heidenmauer or "High Wall", the end of which was marked by two towers, the Stümpert and the Teschenturm. From these end points, the medieval wall almost formed a semicircle. In a south-westerly direction, it ran behind today's Marktkirche church and the town hall along the market square to the Niederpforte gate at the corner of Marktstraße and Mauergasse, first mentioned in 1363. From here, it ran across Ellenbogengasse to the Oberpforte or clock tower on Marktstraße, only to meet the Heidenmauer again in a straight line on Grabenstraße.

The square Stümpert, which was not connected to the Heidenmauer, was first mentioned in 1489. The round Teschenturm, which is mentioned in 1503, dates back to Roman times and was given a wooden superstructure in the Middle Ages. Like the tower still preserved above the "Römertor", which projects in a semicircle in front of the Heidenmauer, the Teschenturm was also known as the "Kessel", a term derived from "castellum".

In 1508, Count Adolf III of Nassau-Idstein (1443-1511) decided to further fortify the town and the "Flecken" because of the "heavy and dwindling run, which causes daily riots". The "Flecken" was added to the west of the narrower urban district in the area of the outer bailey, the "oppidum", as it was called in 1292. The sources also refer to it as the suburb. This second settlement core was included in the walled enclosure in 1508. To the north, beyond the Heidenmauer, lay the Sauerland, named after the salt content of the springs. For this area and its more rural population, a fortification of ponds and ramparts was sufficient until the 18th century.

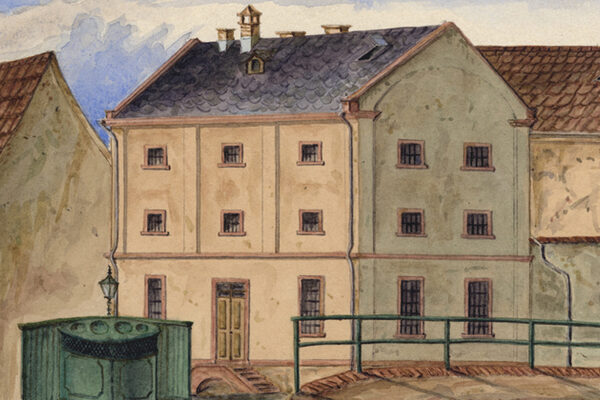

The new wall started at the Niederpforte(town gates), ran along the Mauergasse and its continuation to the Mainzer Tor and later served as the southern wall of the orphanage built in 1725. It then curved beyond Kirchgasse to the Stumpfen Tor, first mentioned in 1477, and from there to the Heidenmauer. By 1609, the entire fortification was already in a very ruinous state. In 1684, the future Prince Georg August Samuel von Nassau-Idstein expressed his displeasure at the state of the gates, moats and walls and six years later issued a decree regulating the repairs to be carried out on the existing fortifications.

On this occasion, the wall was postponed or replaced by the new churchyard wall due to the construction of a new churchyard in the north-west on the Schulberg. The project for a new wall around the Sauerland was then tackled. This new construction was also not to follow the course of the old wall in all cases, but was to be extended behind the hospital on Kranzplatz to create a churchyard for the poor. The project dragged on for over 40 years; the fortification was never fully completed, as the days of solid town walls were long gone by the 18th century.

The dimensions of Wiesbaden's city wall were not very impressive; it was only about 60 cm wide; at a height of 1.58 m there was a wall walk which measured another 60 cm in width; it is not known how high the wall was in total.

There were three manorial mills at the neuralgic points of the town fortifications. It can be assumed that the water damming caused by weirs, which was necessary for the operation of these mills, was also used early on for the defense of the town. These "wet ditches" are first mentioned in the 14th century and have been referred to as ponds since 1448. In the late Middle Ages, four ponds protected the town itself, and 13 of these bodies of water stretched around the town and the Sauerland. Their average width was 14 m, and the sloping terrain allowed the water to flow to the next, lower pond. The transverse dykes or dams that served as boundaries have been called "Schütten" since the 16th century. Footbridges or small bridges led across. The citizens and inhabitants of the surrounding villages were responsible for maintenance, cleaning the ponds of stones, mud and reeds, de-icing in winter and fishing. So-called "Grabenschröder" and pond servants were responsible for supervision. The ponds, which at times represented an important fish reservoir, belonged to the lordship. Only the water in front of the Stumpfen Pforte was municipal.

The largest pond in Wiesbaden was the "Breite or Kalte Weiher". It stretched from the Stumpfen Tor to the Niederpforte and was originally directly adjacent to the city wall. Part of it was drained as early as the 15th century to create meadows and cabbage gardens. In 1591, the Count of Nassau gave it to his bailiff, the owner of the adjacent Koppensteiner Hof, after whom it was called "Koppensteiner Weiher" from the mid-17th century. It was protected from the outside by the Breite Damm, which was documented in 1524 and ran across today's De-Laspée-Straße and Karl-Glässing-Straße to Wilhelmstraße. Around 1750, it was drained and a garden was created, later known as the Dernsche Gelände.

The "Warme Weiher", whose name comes from the thermal water of the bathhouses that flowed into it through Spiegelgasse, was the last body of water to be drained in 1812. Part of its terrain was absorbed into Alleestrasse or Wilhelmstrasse. The name Warmer Damm still reminds us of it.

Literature

Wiesbaden in the Middle Ages. History of the City of Wiesbaden 2, Wiesbaden 1980.