Wiesbaden prince robbery

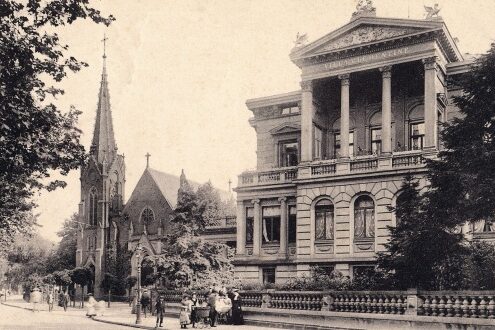

On July 13, 1888, with the support of the local chief of police and the participation of numerous people who had gathered on Wilhelmstrasse, King Milan of Serbia had his son, the 11-year-old Crown Prince Alexander, abducted from the Villa Clementine.

The abduction of the Serbian Crown Prince Alexander Obrenović (1876 -1903), King of Serbia from 1889 to 1903, from the Villa Clementine in Wiesbaden on July 13, 1888 is often referred to as the Wiesbaden Prince Abduction.

According to the treaty concluded in Belgrade on April 6, 1887 by Their Majesties King Milan and Queen Natalie of Serbia, who were separated after personal and political conflicts, Crown Prince Alexander was to be educated from 1887/1888 in a jointly selected city in Germany which, in addition to favorable climatic conditions, was also to have a Serbian or Russian Orthodox church. This was the case with Wiesbaden.

The contract contained far-reaching concessions to Queen Natalie with regard to the crown prince's upbringing: "The crown prince will be under the care of his high mother for the duration of his upbringing, who will live with him for this purpose and also accompany him to Serbia during the vacations." King Milan did not consider the presence of the Queen and the Crown Prince in Belgrade opportune at this time due to possible political unrest.

On June 4, 1888, Queen Natalie informed King Milan that she had "rented a very beautiful villa" in Wiesbaden and would be taking up residence here. Her intention to travel to Belgrade after moving into Villa Clementine in the summer of 1888 was firmly rejected by King Milan, who informed her that he had applied to the Holy National Church for a divorce.

When Queen Natalie rejected this request, King Milan demanded in return in a dispatch dated 14 June that Natalie should recognize him as "husband and father" and prove this by allowing the crown prince to leave for Belgrade without her escort. "The foreign government is prepared to send the prince here..." If Natalie did not agree, he would return his son by force and if it occurred to her to come to Belgrade with him, he would take him from her by force and obtain a divorce. In a new draft agreement, Queen Natalie was to undertake "never to come to Serbia without a special invitation from the king until the crown prince had reached the age of majority." She was to remain resident in Wiesbaden with the crown prince until January 1, 1893 and not change her residence without the king's written consent. However, Natalie rejected this contract already signed by Milan, "to Wiesbaden" and "to Belgrade". However, she did not have much time to think about it, because on June 20, Milan sent the "definitive and irrevocable instruction" to the Serbian Minister of War, General Protić, to order a special train for the Crown Prince's departure. Protić was to go to the President of the Government in Wiesbaden the next day to inform him of the train's departure and to ask him for assistance in the event that the Queen resisted the order received. Milan gave her a final ultimatum to agree to the presented treaty by six o'clock in the evening of the next day, but Queen Natalie still refused.

On the eve of July 13, 1888 - it was a Friday - Chief of Police Paul von Rheinbaben went to Villa Clementine, which had been heavily guarded for days, to inform the queen that the crown prince would be taken away the next morning at ten o'clock "if necessary by force ...". She herself was expelled and had to leave Germany ten hours after the prince's departure. King Milan had achieved this by intervening with Kaiser Wilhelm II and Chancellor von Bismarck, while the Queen's appeals for help to the ruling dynasties went unheeded. In a personal telegram, Kaiser Wilhelm II asked her to give up her resistance and "... willingly hand him over to the plenipotentiary of the royal father."

Since the early morning of July 13, the Villa Clementine had been shielded by a detachment of guards and secret police. Shortly before ten o'clock, Major Chiević and Lieutenant-Colonel Bjalović, who had been appointed aides-de-camp to the Crown Prince by King Milan, went to the villa to report to the eleven-year-old royal highness. Shortly after ten o'clock, the chief of police drove up, followed by a police inspector, two commissioners and twelve guards. After a brief negotiation, the prince was handed over to General Protić, then taken to the Taunus station in a carriage and brought to Belgrade with his aides in a saloon car attached to a scheduled train.

The political background to the abduction of the crown prince only became clear later, when King Milan abdicated unexpectedly in February 1889 and had his underage son proclaimed King Alexander I of Serbia. Alexander was given three "regents" to run the affairs of state while the young king lived like a prisoner in the Konak, the royal palace in Belgrade.

Secret agreements with the regents, which only became known later, ensured that Milan, who lived mainly in the Austrian Puster Valley until his death in 1901, had a decisive influence on Serbian politics behind the backs of the public and his political opponents, even after his abdication.

Literature

- Königin Nathlie von Serbien

Memoirs, Berlin 1891.

- Königin Nathlie von Serbien

From the diary of Queen Nathalie, experiences of the Serbian regent according to authentic sources, communicated by Heinrich Büttner, Berlin 1891.

- Forßbohm, Brigitte

The abduction of Crown Prince Alexander. An act in the Serbian "royal tragedy". In: Crimes and Fates. A Wiesbaden Pitaval. Fuchs, Hans-Jürgen (ed.), Wiesbaden 2005 (pp. 83 - 98)